(by Corbo Eng)

In “According to What?,” Ai Weiwei’s retrospective show, now, at the Hirshhorn Museum in DC, the confluence of art and politics that so characterizes Ai’s oeuvre is on undeniable display—so much so that knowledge of Ai’s various roles as dissident and artist is tantamount to the exhibition’s admission ticket. This circumstance is inescapable. To appreciate Ai’s multifaceted work is to first know the man—and to know him in the context of his struggle with the Chinese authorities: a struggle, which, like blood running through his veins, defines his work and output. That struggle, which Ai has carried on most intensely since 2008, at times, results in variably overt or less direct jabs; but, seemingly, a statement is ever present.

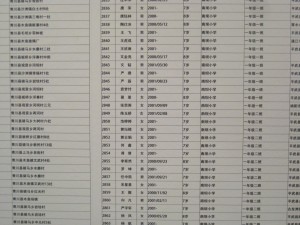

A section of “Names of Student Earthquake Victims Found by the Citizens’ Investigation” (2008 – 2011)

For example, in the aftermath of the great Sichuan Earthquake of 2008, when thousands of school children perished in shoddily built school buildings, an outraged Ai gathered the names of the victims in an engrossing piece entitled, “Names of Student Earthquake Victims Found by the Citizens’ Investigation,” which at the Hirshhorn, takes up an entire second floor wall. As a scathing indictment, the more than 5,000 names cry out figuratively and literally as bureaucratic Chinese characters record the names of the dead and a stark recorded voice (a separate work entitled, “Remembrance”), reading the names, plays eerily in the background.

A related piece, called “Snake Ceiling,” continues the protestation. Made from identical black, white, and green interlocking backpacks, like those worn by school children, the work ostensibly forms a giant snake and hangs from the ceiling (twisting and coiling menacingly through an adjoining hallway—and past those aforementioned names); but, as well, it is a commentary on the Chinese authorities who continue to “snake” their way out of any culpability. “Straight” features a huge pile of rusted steel rebar that was collected from the twisted rubble of the school buildings. The arranged metal, which meanders on the gallery floor, features rolling bumps, rises, and fissures. At once, the sculpture can be read as a representation of the earthquake itself across a broken surface of land or as a disturbing seismic record of the event. Another work, also displayed on the floor and continuing in the mold of sly invective, is “He Xie,” which, on its surface, may be quite puzzling. The work, taken at face value, is basically a spread of 3,000 porcelain crabs. In fact, “he xie” means “river crabs.” However, in Chinese, “river crab” is a homophone for “harmony,” which is used as a euphemism for censorship.

Other works quarrel not with the government’s indifference or mistreatment of its people but with its disregard for the past and what is lost in China’s now rapid growth. This is seen most iconically in Ai’s photographic triptych, “Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn,” which captures, in three panels, images of him holding an urn, dropping it, and standing over it as it is smashed in unforgiving pieces on the ground. A series of Han Dynasty vases, just in front of the three photos, called appropriately, “Colored Vases,” feature 16 ancient vases that have been dipped into various hues of bombastic industrial paint. Another vase, dating further back to Neolithic times (between 3,000 and 5,000 BC), incredulously, has the familiar Coca-Cola script painted on it.

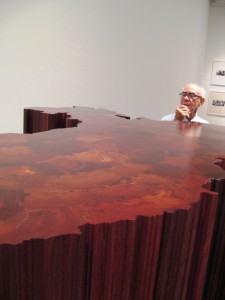

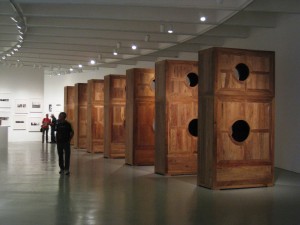

Many other works comment on this defiling of the past in more subtle ways. A number of them showcase Ai’s craftsmanship as he reworks dark, burgundy Tieli wood gathered from Qing Dynasty temples that have been unceremoniously dismantled or bulldozed over. The discarded wood is given grand rebirth. One such work, entitled, “Map of China” is a four feet tall, regal surface cutout of the country made from joined columns of wood. “China Log,” which also is made from meticulously joined columns, appears to be a long, ordinary pillar lying on the floor; but, upon peering down its cross section, a cutout of China again can be seen where a circular hole might otherwise have stretched lengthwise into the interior.

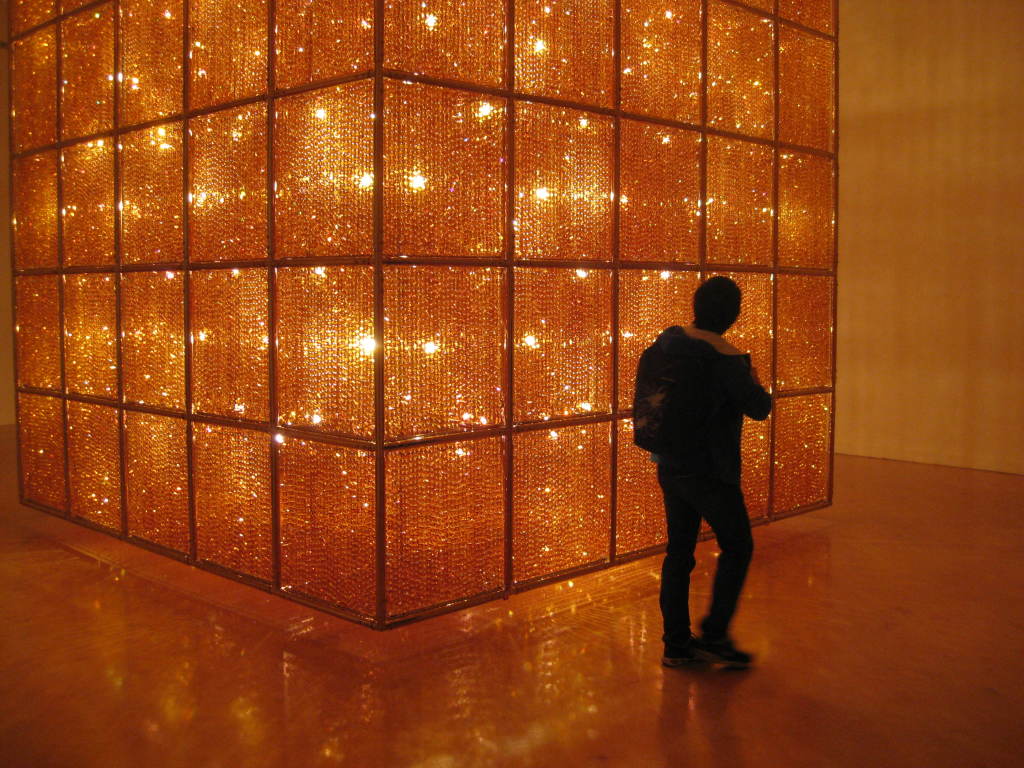

Throughout the exhibition, more straightforward artworks dot the assembled galleries. These occupy the more subtle end of the spectrum and capture Ai in a less politically overt mood. “Moon Chest,” “Cube in Ebony,” “Grapes,” and “Teahouse” all highlight Ai’s artistic sensibilities first and foremost as he takes, in turn, huali wood, rosewood, wooden stools, and compressed tea leaves and transforms them into beautifully minimalistic works that can be appreciated without much of a political backstory or a heightened awareness of his biography. “Cube Light,” one of the more popular works in the exhibition, is a towering illuminated cube made from panels of golden glass crystals. Here, Ai’s unadulterated artistic vision, with a wash of golden light condensing into the room, is most clearly on display.

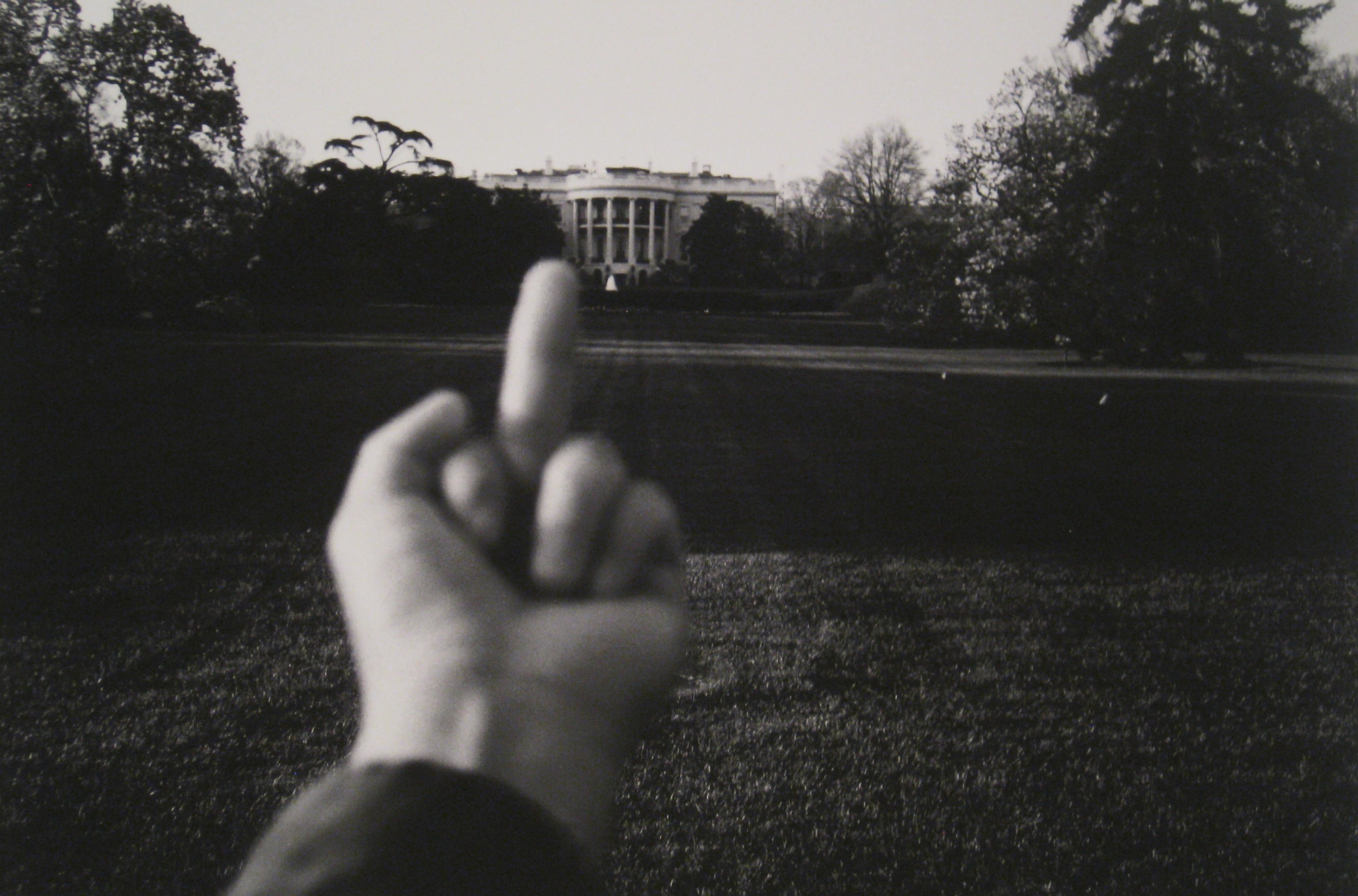

Photographic images, also, play a key role in the exhibit. A large section is devoted to black and white photographs from 1983 – 1993, when Ai lived in New York City. Here, in this gallery, visitors can see Ai standing in front of various Manhattan locales, sitting on the toilet in his apartment’s bathroom, or posing with noted figures (such as a photo with Allen Ginsberg from 1988). Another gallery, further along in the curving Hirshhorn exhibition space, feature more pictures to ponder—photographic tweets and other assorted images.

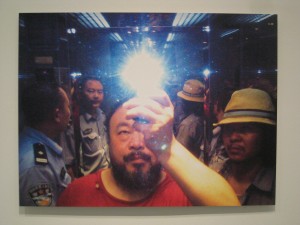

One famous example is Ai’s selfie from 2009, which he took from an elevator’s mirror as he was taken into custody by the police. Other notable photos continue the ongoing theme of political oppression and political protest. There is a blown-up image of Ai’s MRI, entitled “Brain Inflation,” that shows the cerebral hemorrhaging that he suffered after being violently beaten by police in Chengdu. Another image, hung near the second floor exit—and, certainly, all the more potent due to its present context—is Ai’s work sardonically entitled, “Study of Perspective: White House,” which shows a close-up of Ai’s hand as he flips off the White House, in the distance, with his middle finger.

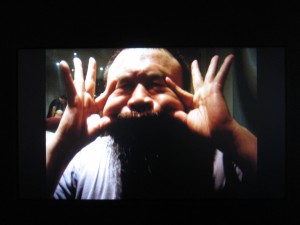

Then, on the third floor, a video display, entitled “258 Fake” (named for the street address where Ai’s Beijing architectural studio “Fake” is located) serves as a kind-of denouement for the entire exhibit. It spans 12 video monitors, lined up in a linear, horizontal spread against the wall. To follow and absorb the imagery, visitors are essentially forced to choose a screen at random to focus on—with unavoidable peeping and peering across at the other screens as the image before one’s eyes stays put for its 30 second duration. The images, as a whole, are inarguably irreverent—with Ai hamming it up for the camera: posing with nostrils flared, eyes agape, or with his face, otherwise, contorted for the lens.

Many of the photos, given a copious tally of the thousands of included images, interestingly, are of food—presumably, pictures taken of Ai’s meals at home and when on travel. There are the requisite photos of Chinese food, as would be expected, and other Asian foods—Japanese, in particular; but, other images pop up as well—indecipherable photos to be filed under molecular gastronomy, pictures of olives, snapshots of home fries and donut holes. To assign Ai with yet one more label: foodie—might not be a stretch at all.

In total, “According to What?,” taken in its entirety, is an absorbing and time consuming account of one of the world’s foremost artists. The casual, walk-in-off-the-National Mall-museum-goer may find the exhibition to be a head-scratcher and a convenient excuse to hurry across the street to the Air and Space Museum. However, for those inclined to fathom its messages, contradictions, and absurdities, the payoff is, most definitely, there.

Copyright 2013 (Corbo Eng). All rights reserved.

All Photos by Corbo Eng (taken at the Hirshhorn Museum of Art).