(by Corbo Eng)

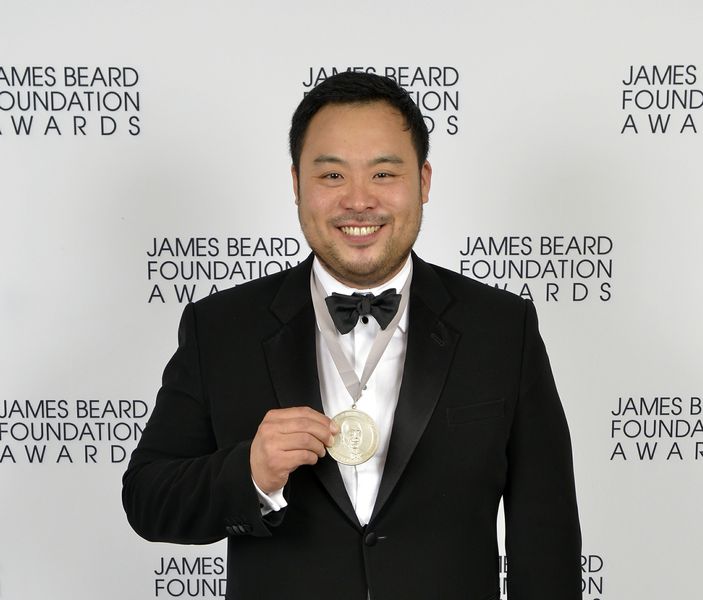

It was the night of May 6, 2013.¬Ý He wore a tuxedo and looked as sharp as a tack‚Äîexuding a sense of pride and nervous excitement that accepting a James Beard Award might very well inspire.¬Ý After all, David Chang, at age 35, was at Lincoln Center¬Ýin New York, on the largest stage the food and restaurant industry had to offer‚Äîbefore a packed house of his peers; and, he was being anointed as the most outstanding chef in the country.¬Ý While only those who have won such an honor can attest to how deeply rewarding it really must be‚Äîsuffice it to say, it had to be a singularly joyful and affirming moment (even as there was a rare tie that resulted in two awardees: Chang and Paul Kahan).

However, Chang, being gracious in the moment and feeling reassured by a friendly presence, remarked, ‚ÄúA tie couldn‚Äôt have been better because I‚Äôm not here by myself.‚Äù¬Ý He seemed to relish the fact that he hadn‚Äôt been singled out and that all of the spotlight wasn‚Äôt focused solely on him.¬Ý Surely, in his mind, having two outstanding chefs and sharing the distinction couldn‚Äôt have been a blemish in any way or the result of a horrible miscount of the vote.¬Ý This wasn‚Äôt a presidential election after all.¬Ý Different rules applied; and, therefore, in this particular circumstance,¬Ýthere was no mistake.¬Ý However, for David Chang, it probably wouldn‚Äôt have mattered anyway even if there had been one.

For a chef who has, in less than a decade, captured the imagination of a food-loving public, created a restaurant empire for himself, gained undeniable celebrity status, and redefined Asian-American cuisine, he has been, on the whole, remarkably humble—embracing making mistakes in a way that can only be regarded as a personal philosophy (a kind of paradoxical badge of honor that is analogous to Rodney Dangerfield’s life-giving lack of respect).

How did this start?¬Ý Perhaps, it can be traced back to the fact that Chang never felt that he was qualified to open a restaurant in the first place.¬Ý As a young, aspiring chef, he had, in an act of self-making,¬Ýtraveled¬Ýto Tokyo to discover ramen and, once back home, enrolled at the French Culinary Institute, finished his program, and had¬Ýshort, seemingly uneventful stints at the Mercer Kitchen, Craft, and Caf√© Boulud‚Äîwhere, in the latter restaurant, he worked¬Ýunder noted chef, Andrew Carmellini.

Chang admitted, in his cookbook, ‚ÄúMomofuku,‚Äù published in 2009, that this piecemeal path had ‚Äústunted his growth‚Äù because he hadn‚Äôt apprenticed¬Ýand learned under any one chef long enough.¬Ý He had opened Momofuku Noodle Bar (his first restaurant), after leaving Caf√© Boulud, even if common sense had dictated that he shouldn‚Äôt have; and, resultingly, from the outset, he had a nagging feeling of doubt and unease as he forged ahead as his own man.¬Ý What fueled him, therefore, was ambition and, perhaps, more so, a desire not to fail as everyone around him expected.¬Ý But, in those early days of Noodle Bar, the challenges were considerable.¬Ý Chang and his, then, business partner Jaoquin Baca couldn‚Äôt sustain a core staff of cooks and other hired help and ran themselves ragged in the process: fixing things, taking orders, cooking, cleaning, washing dishes, and doing whatever else was necessary (seemingly, all on their own).

Noodle Bar, also, at that point had not started to make its own noodles‚Äîalkaline noodles, more specifically, and were still relying on a Chinatown supplier for what amounted to lo-mein noodles (which were intended for stir-frying and not soups).¬Ý With an inferior product and lackluster business, the outlook didn’t seem bright.¬Ý However, Chang, understandably, refused to deviate from the concept of a ‚Äúnoodle bar‚Äù (trying, as best as he could, to remain faithful to his original inspiration‚Äîthat of the many ramen shops that he had visited and which had left their marks on him while he was in Japan).

However, it was not until Chang had reached a desperate point and saw no other option that he decided to modify his original concept (not even a year into its existence) and cook and sell what their abilities and the nearby Greenmarket would fully allow that the restaurant finally thwarted the impending¬Ýprospect of going-out-of-business and became a success (and, a huge one at that) with decidedly non-Asian ingredients like sweetbreads and headcheese, for example, on the menu¬Ýgarnering praise.¬Ý It was a turning point.

Frankly,¬Ýwhen¬Ýa food historian,¬Ýone day, writes the history of Asian¬Ýfood in America and¬Ýattempts to identify that one watershed moment, when the zeitgeist was¬Ýseized and¬ÝAsian food, long associated with Americanized Chinese food¬Ýor even badly made supermarket-grade sushi,¬Ýbecame hip in this country, it might have been when Noodle Bar ceased to be a categorically restrictive place‚Äîsometime, as 2005 began.¬Ý¬ÝAt that moment, Chang‚Äôs hard work paid off as he recognized¬Ýhis miscalculation, moved to rectify his mistake, and,¬Ýlike the¬Ýcoach of a losing football team,¬Ýallowed his chefs¬Ýto cook¬Ýwithout any preconceived notion of what Noodle Bar should be or what influences it could embrace.¬Ý¬ÝChang,¬Ýin football terms, had thrown away his original playbook and revamped his¬Ýsystem to best¬Ýutilize the talent of his players.

Sidestepping happenstance, for sure,¬ÝChang saved Noodle Bar from what seemed like certain¬Ýdefeat.¬Ý In conveying the force behind its saving and, frankly, what had brought him to where he was¬Ýat that point‚Äîas a burgeoning¬Ýfigure of note on the national scene, Chang spoke in explicit terms as he sat down with Charlie Rose on his show in 2008. ¬ÝIt was part coachspeak, part confirmation from within.¬Ý “You just have to go for it,” he told Rose. ¬Ý“You¬Ýgot to go for broke.¬Ý¬ÝYou got to go all in sometimes.”¬Ý¬ÝIt was so apropos.¬Ý “You can‚Äôt play to lose.¬Ý You have to play to win‚ĶYou have to make some bold decisions.”¬Ý It was as if Chang were, in some sense,¬Ýa “culinary Bill¬ÝBelichick”¬Ý(minus the hoodie, of course)‚Äîhaving decided on making that bold decision on fourth down in order to win rather than safely punt and lose.¬Ý Clearly, he had the success and multiple restaurants at that point to show for it.

Chang,¬Ýfinding sure footing as his¬Ýinterview with Charlie Rose progressed,¬Ýremarked confidently and in, now, unmistakable and characteristic fashion: “Sometimes,¬Ýthere are mistakes; and, you have to make mistakes.¬Ý That‚Äôs the only thing.¬Ý It‚Äôs sort of clich√© to say but we make a lot of mistakes.”¬Ý There was a gleam in Chang’s eye‚Äîa look that, even as a young man, suggested that he had stumbled upon real wisdom, upon something true that only real experience could have birthed.¬Ý He continued, “That‚Äôs what I used to tell the cooks‚ĶI don‚Äôt care if you screw it up.¬Ý But, make sure you know why you made that mistake; and, let‚Äôs not make it again‚Ķjust don‚Äôt make them the second or third time around.”

Of course, it was fitting,¬Ýgiven the necessity of making mistakes in the Changian construct of success, that Chang did actually make the ‚Äúsame mistake‚Äù the second time around (ignoring irony, for the moment) when he opened Momofuku Ss√§m Bar, his second restaurant.¬Ý¬ÝChang‚Äôs initial vision was to open a sort of fast casual/fast food establishment and become a purveyor of Korean-style ss√§ms (ss√§m‚Äîmeaning ‚Äúwrap‚Äù in Korean).¬Ý In his new concept,¬Ýrather than using different kinds of lettuce leaves to do the wrapping (as is traditional with Korean ss√§ms and as is common at Korean BBQ restaurants, for instance), Chang‚Äôs plan was to use flour tortillas instead and to concoct a product that was more of a ss√§m-burrito hybrid that would feature distinctively Asian-inspired ingredients such as edamame, kimchi, pickled shiitakes, hoisin sauce, rice, of course, and Noodle Bar‚Äôs ubiquitous shredded pork shoulder.

Admittedly, It was a clear enough concept‚Äîone that he hoped to parlay into Ss√§m Bars across the country.¬Ý It was ingenious‚Äîexcept that, once Momofuku Ss√§m Bar opened, the ss√§m-burritos weren‚Äôt popular; but, the restaurant‚Äôs promise and success was predicated on those ss√§ms.¬Ý It was called, ‚ÄúMomofuku Ss√§m Bar‚Äù after all.¬Ý As with Noodle Bar, Chang was faced with the prospect of his restaurant going out-of-business if he didn‚Äôt change course.¬Ý However, like a great coach or an improvising¬Ýjazz musician for that matter, Chang abandoned his original game plan once again or¬Ýthe guidance of his¬Ýsheet music, as the case may have been, and¬Ýbegan to offer an eclectic menu‚Äîone that tapped into the strengths of his cooks, such as Tien Ho.¬Ý Seemingly at a moment‚Äôs notice, Chang reinvented Ss√§m Bar and began selling terrines, Vietnamese-inspired fare, and the now famous country hams.¬Ý The new offerings struck a chord with diners, and Ss√§m Bar finally took off.¬Ý And, that‚Äôs where the irony was‚Äîwithout ss√§ms playing a role at all.

In a way, what happened at Ss√§m Bar was, perhaps, Chang‚Äôs quintessential mistake.¬Ý Without proper testing, research, and planning, he banked everything on selling fusion-Korean burritos‚Äîwhich, ultimately, nobody really wanted.¬Ý Such a scenario, certainly, had disaster written all over it; but,¬Ýit was a ‚Äúmistake‚Äù turned on its head‚Äîand, which, looking back, precipitated an unlikely but bold¬Ýsuccess.¬Ý The marriage between¬ÝChang‚Äôs French and American culinary influences and Asian ingredients¬Ýexperienced their finest incarnation at Ss√§m Bar.¬Ý And, it was there, as the restaurant grew and matured‚Äîinto something decidedly more substantial and elegant than a burrito bar‚Äîthat the vanguard of new Asian-American food found brilliant expression when such expression was needed.¬Ý Instead of going the way of the Dodo bird, Ss√§m Bar went on to earn multiple Michelin stars and a place on San Pellegrino‚Äôs list of the 50 best restaurants in the world.¬Ý Chang had the Midas touch.¬Ý It was one thing to make a mistake and to overcome it‚Äîjust to survive; but, his mistake, in this case, had turned inexplicably golden.

In 2012, as a guest on the Paul Holdengr√§ber Show, an internet¬Ýprogram on the Intelligent Channel, Chang, who had majored in religious studies¬Ýat Trinity College in Connecticut as an undergraduate,¬Ýwas questioned about¬ÝThomas Bernhard, Henry David Thoreau, and The Social Contract‚Äîcertainly, not your usual topics involving pork buns, fermentation, or the merits of MSG.¬Ý¬ÝHowever, interspersed between what was some very heavy philosophical musings,¬ÝChang managed to comment¬Ýon¬Ýhis career, ‚ÄúFor me, I‚Äôm always trying to reconcile the past.¬Ý I‚Äôm always looking at mistakes I‚Äôve made‚ĶNo one‚Äôs going to spoon feed you‚ĶNobody‚Äôs going to teach you anything.¬Ý You got to grab it‚ĶYou got to go big.¬Ý You got to fuck up.¬Ý You have to.¬Ý You‚Äôre not going to learn‚Ķif you don‚Äôt burn yourself.‚Äù¬Ý Chang was entirely in character‚Äîespousing, as he was, that familiar Changian ethos of self-determination, which was all¬Ýheightened by the¬Ýbeneficial prospect of¬Ýmaking mistakes.

It‚Äôs safe to say that, if Chang hadn‚Äôt ‚Äúgrabbed it‚Äù in revamping Ss√§m Bar and it had failed, the Momofuku story might have been entirely different‚Äîone where a determined attitude likely would have been ever present but one where mistakes would have been more likely debilitating than redemptive.¬Ý All of the pieces that followed in such rapid succession‚ÄîMomofuku Ko in 2008, the Momofuku Milk Bar locations that sprang up around New York (of which there are six presently), M√° P√™che in Mid-town in 2010, Momofuku Sei≈çbo in Sydney in 2011, the launch of Lucky Peach, a new quarterly food journal in 2011, Booker and Dax (a bar by Dave Arnold at Ss√§m Bar) in 2012, and Momofuku Toronto (consisting of a new Momofuku Noodle Bar outlet, Nikai, Daish≈ç and Sh≈çt≈ç) in 2012‚Äîmight never have happened.¬Ý Chang would have assuredly done something else to grow his business beyond the original Noodle Bar if Ss√§m Bar had crashed and burned; his self-determination would have seen to that.¬Ý But, it‚Äôs easy to imagine the Momofuku empire being, as a consequence, a completely different, more pared down entity, on a less grand scale.

Of course, that is all conjecture because the Momofuku empire is anything but pared down at this point; and, with Chang‚Äôs most recent venture embodied in a brand spanking new, modernist edifice in downtown Toronto that has been dubbed the ‚Äúglass cube‚Äù (consisting of three floors, 30,000 square feet, three new restaurants, and one bar/lounge), the empire-building as of late has been decidedly grand, indeed.¬Ý For any chef or restaurateur, biting off so much at once would have been quite daunting‚Äîwith challenges that would be unique to such a huge endeavor.¬Ý For David Chang, as one who is unafraid of mistakes and who, seemingly courts them, the prospect of making mistakes on, perhaps, an exponential scale‚Äîwith four places opening all at once‚Äîmust surely have been nerve-wracking to say the least (but, surely, not in a prohibitive way).¬Ý Maybe, just as an ambitious juggler might desire a few chainsaws thrown in with the run-of-the-mill rubber balls that he routinely juggles (and, tempting fate with the distinct possibility of shearing off his hands or head) for the sake of becoming¬Ýbetter, Chang may very well have embraced Toronto in a similar vein.

In fact, in his conversation with Steve Dolinsky of Chicago‚Äôs ABC affiliate last year, as Dolinsky peppered him with questions about expanding Momofuku to Chicago, Chang explained why he chose to expand to Toronto as he did.¬Ý ‚ÄúWe just don‚Äôt have the opportunities to go into a new building in New York that sort of gives us this space‚Ķwe could never do something in a large space‚Ķmore importantly, getting everything new: new pipes, new water mains, new everything is really exciting‚Ķthat‚Äôs the stuff that breaks all the time in New York‚Ķto carve out a new space was really exciting.‚Äù¬Ý So, the newness and the magnitude of the space in Toronto carried some weight (contrasting as it does with Chang‚Äôs older properties in New York); but, as Dolinsky continued to press on with his questioning, Chang revealed something more, something central.

‚ÄúThis is an opportunity to do something where‚Ķwe have room to make mistakes.¬Ý You know, that‚Äôs very important to me‚ĶWhen you‚Äôre under the spotlight, whether it‚Äôs in New York or Chicago or, let‚Äôs just say we open up in London [where] the scrutiny is so intense, it‚Äôs hard to grow.¬Ý And, you can‚Äôt grow unless you make mistakes‚ĶYou need that incubation period to really find your voice and to grow.‚Äù¬Ý What Chang wanted, then, was the relative obscurity of the Toronto food scene where he and his staff could learn from their mistakes without too much scrutiny.¬Ý He was speaking in very Changian terms; but, then, there was a bluntly worded clincher.¬Ý ‚ÄúYou know, if Jos√© [Andr√©s] is known for modern gastronomy, Ren√© [Redzepi] is known for terroir foraging and bringing that together in Scandinavia,‚Äù Chang explained emphatically.¬Ý ‚ÄúWe want to be the king of mistakes.‚Äù¬Ý The pithiness of the remark, the sense of irony in it (as if anybody would really want to be that), and its identity-giving properties gave it immediate import‚Äîand, in only a way that David Chang and his worldview could make believable.

When Zero Point Zero, the production company behind all of Anthony Bourdain‚Äôs successful shows, launched a new series called ‚ÄúThe Mind of a Chef‚Äù on PBS in the fall of 2012 (with none other than Bourdain himself as narrator and executive producer), the focus of the first season‚Äôs 16 episodes was Chang‚Äîwho was, now, a bona fide TV star (if not an aspiring ‚ÄúKing of Mistakes‚Äù as well).¬Ý The show‚Äôs format was a mix of travelogue, personal history, and cooking demonstrations‚Äîall informed by Chang‚Äôs culinary influences and interests.¬Ý Among the places that the show examined was, of course, Japan‚Äîwhere Chang¬Ýreverentially indulged in ramen.¬Ý However, Chang explored other locations as well‚Äîsuch as when he foraged for food with Ren√© Redzepi in Copenhagen and when he sampled pinchos with Juan Mari Arzak in San Sebasti√°n, Spain.¬Ý Other episodes, with varying levels of specificity, revealed Chang‚Äôs love of pork, smoked meats‚Äîincluding Alan Benton‚Äôs bacon, steamed blue crabs from his days as a child growing up in Northern Virginia, and, not unexpectedly, instant ramen‚Äîwhich Chang, not knowing any better (and, making a mistake), used to eat without broth like a giant dehydrated cracker.

Of course, the show could not have aired 16 installments without¬ÝDavid¬ÝChang making explicit mention of mistakes‚Äîwhich he did in episode 12 (entitled, ‚ÄúFresh‚Äù and which explored the idea of freshness in food).¬Ý At one point in the episode, along with segments on ikejime, a method of paralyzing fish to maintain quality, and dry-aging meat, Chang, along with¬ÝDaniel Burns who was then the head of research and development at the¬ÝMomofuku Culinary Lab, demonstrated how they had sped up the making¬Ýand intensified the flavor of Momofuku‚Äôs ramen stock by first freeze-drying the constituent shitakes, chicken, and pork, which, when turned into powdered form, was added to boiling water.¬Ý¬ÝOnce poured out over a fine sieve, the clear stock became the glorious end product; and, the ‚Äúsludge‚Äù in the mesh of the sieve, collected from the spent shitake, chicken, and pork powders (which Chang thought to instinctively discard) became, for Burns, the inspiration for a new creation‚Äîcalled, ‚Äúmushroom chips.‚Äù

Burns, at the time, thinking there was something useful in that sludge (and extending the spirit of experimentation that is at the heart of any test kitchen), had rolled it out onto a non-stick baking mat and placed it in a dehydrator where it was, thusly, transformed into something crispy‚Äîsomething that looked like a gossamer sheet of toffee.¬Ý When it was snapped and broken into pieces (‚Äúchips‚Äù), Burns discovered that it was full of umami (that elusive but cherished ‚Äúsixth flavor‚Äù that so many chefs seek to create in their food).

‚ÄúYou never know what gold you can dig up out of total garbage/trash, and that gold came from trying to make a stock that we all were laughing about,‚Äù Chang said in explaining the origins of the mushroom chips.¬Ý Then, he got into character and expounded on mistakes.¬Ý However, this¬Ýtime,¬Ýunlike on previous occasions, his words were¬Ýdirective, specific,¬Ýand¬Ýquasi-systematic in an almost teacherly way.¬Ý¬Ý‚ÄúOnce you make that mistake, keep a journal of how you made those mistakes.¬Ý Then, you can sort of chart your growth in terms of how things were made.‚Äù¬Ý To tie the lesson in error into a tidy summary,¬ÝChang evoked‚Äîof all people‚ÄîJames Joyce who, more often than not (if Ulysses and Finnegan‚Äôs Wake are any examples), is mostly incomprehensible¬Ýbut who, in Chang‚Äôs mind (at least, in this¬Ýinstance), perfectly punctuated the moment.¬Ý Quoting¬ÝJoyce, Chang asserted confidently,¬Ý“Errors are the portals to discovery.‚Äù

However, this¬Ýopenness to discovery, this error-making, and ancillary journal-keeping is¬Ýa¬Ýrather nonlinear and unpredictable¬Ýprocess of…yes, making mistakes.¬Ý Of course, for Chang, that’s the fun of it, no doubt.¬Ý Indeed, the¬Ýessence of what it means to cook‚Äîwith the mission of pleasing the customer always at¬Ýplay‚Äîis to¬Ýdiscover¬Ýthat next flavor combination¬Ýand to¬Ýmake¬Ýa¬Ýnoteworthy dish (something, perhaps, more of an entr√©e than simply a garnishing mushroom chip) no matter how difficult and cumbersome it may¬Ýpotentially be.¬Ý¬ÝIn the end, Chang himself understood that.

“There’s no genius chef,” Chang stated recently.¬Ý He seemed as resolutely confident as ever in his remark.¬Ý “There’s nobody¬Ýthat’s just born out of the womb that can do it…like, I think, you have to sort of, like a scientist, just continue to make mistake after mistake after mistake and keep track of that…But, that’s what we want.”¬Ý If nothing else, in words and deeds, it¬Ýseemed to be both tedious and hard‚Äîbut, as a challenge,¬Ýsomething quintessentially Changian¬Ýat its core.

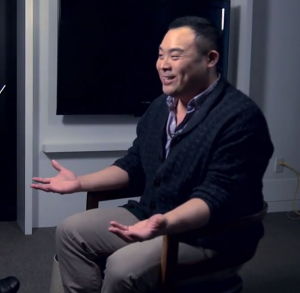

These remarks came¬Ýas Chang, in his usual, collegial manner, sat down¬Ýwith Adam Savage of¬ÝMythbusters fame on his new web series, The Talking Room.¬Ý There, in subdued lighting in Savage’s personal library¬Ýand surrounded by¬Ýshelves of books that¬Ýframed their conversation, Chang, at one point, responded to a question by referring to¬ÝPascal Barbot, the famed chef at L’Astrance in Paris.¬Ý Yes, he lacked genius (as Chang’s¬Ýaforementioned quote indicated); however,¬ÝChang, affectionately¬Ýgushed about¬ÝBarbot’s deficit of genius (in a way that we would all aspire to)‚Äîparticularly,¬Ýas it is manifested in Barbot’s¬Ýsignature foie gras and white mushroom¬Ý“pie” (which consists of layers of foie marinated in verjuice and shaved mushrooms that is¬Ýplated with a blotch of roasted lemon pur√©e and an enticing¬Ýdrizzle of hazelnut oil).

How did such a seemingly haphazard but utterly delicious assemblage of ingredients come to be?¬Ý¬ÝApparently,¬ÝChang was convinced that it must have taken Barbot years of “accidents” to conceive of it.¬Ý “When you eat it…you realize like, this guy’s been working on this dish in his head for years…Of course, he has.¬Ý It happens by accident…it’s a series of accidents.”¬Ý¬ÝIt was Barbot’s “big mistake.”¬Ý And, Chang,¬Ýgesturing and scratching his head, wanted his.¬Ý¬ÝSavage was scratching his head as well.¬Ý “But, doesn’t that become a difficult thing,” Savage asked.¬Ý “To¬Ýmaintain an atmosphere¬Ýwhere the mistakes can yield the accidents that yield the really exciting discoveries?”

Chang, acknowledging¬Ýthat difficulty, especially as Momofuku has grown so large,¬Ýoffered the confession that¬Ýit’s really “embracing the inefficiencies” that leads to the kind of discovery that he wants‚Äîand not the¬Ýconvenient solutions that would be¬Ýreadily available.¬Ý He disdainfully pointed to the example of not wanting to put “a trio of Wagyu sliders on the menu” and “with¬Ýthree different kinds of ketchup” because it would be too easy…too efficient and, ultimately, too safe, too sterile, too free of the mistake making that characterizes, in Chang’s mind,¬Ýthe essence of culinary creativity.

“That is like the lowest hanging fruit type of thing, Chang explained plaintively.¬Ý “The efficiency of that…we don’t want.¬Ý We want…to try to make a dish or struggle for it; and it might take a much longer time, but you’re going to create a much more beautiful, more delicious, more memorable dish by sort of making mistakes along the way.”¬Ý It was an explanation that felt very much at home; but, surely, for those¬Ýunfamiliar with¬ÝChang’s way of working,¬Ýit must surely have sounded¬Ýcounterintuitive to want to be inefficient.¬Ý What kind of business model is that?

But, of course, as one who wants to be¬Ýthe “King of Mistakes,”¬Ýas Chang has so dutifully admitted, he¬Ýmust surely welcome¬Ýthe messy, fussy, convoluted path. ¬ÝNearing the end of their conversation, Chang, looking at peace, boiled it all down and said to¬ÝSavage, “We’re after the big mistake.”¬Ý¬ÝReally, could he have been in search of¬Ýanything else?¬Ý¬ÝIt was¬Ýbold and sounded like everything that an interviewer of David Chang would have wanted to hear.¬Ý¬ÝChang, then, asserted strongly with a magnificently¬Ýconcise¬Ýline, “I think¬Ýflavor actually comes from failure.”

In the end, those words, despite its definite allure, might ultimately lose out to some phrase with “mistake” in its wording¬Ý(of which several good ones appear in the preceding paragraphs) if Chang ever got around to choosing a title for his autobiography (if and when he ever writes it).¬Ý¬ÝThey¬Ýwould have to.¬Ý¬ÝBut, they ring ever true given what we know about David Chang and his philosophy.¬Ý If flavor is what we¬Ýwant when we dine at any of the Momofuku restaurants, then,¬Ýwe also know‚Äîif we encounter it‚Äîthat it didn’t just pop up out of thin air.¬Ý¬ÝMuch trial and error would have, invariably, gone into its¬Ýmaking.¬Ý¬ÝIt’s¬Ýnot unlike a¬Ýcoach who, after¬Ýa few losing seasons under his¬Ýbelt, gets his act together and wins the Super Bowl.

Nobody’s¬Ýa genius; and,¬Ýmost of us aren‚Äôt chefs, nor do we plan to open a restaurant any time soon; but, the mistakes involved are as potentially universal as eating.¬Ý David Chang‚ÄîJames Beard Award winning¬Ýchef and de facto¬ÝKing of Mistakes‚Äîhas tapped into a winning formula by pushing himself hard and‚Ķwell, fucking up once in a while.¬Ý And, that‚Äôs okay.¬Ý We, who have enjoyed his food, have all benefited from his mistakes.¬Ý Let‚Äôs hope that he continues making them.

Copyright 2013 (Corbo Eng). ¬ÝAll Rights Reserved.

All images are screenshots (unless otherwise stated).