(by Corbo Eng)

Catzie Vilayphonh speaks into a microphone…and, not timidly. Imagine a lion roaring rather than a bird nesting in a tree. In performance, she’s not sitting in a chair at Barnes & Noble—daintily reciting verses from a book. In her brand of spoken word poetry, the object is to stand, emote, and strongly express what mere words on paper cannot. Words are enunciated; nouns are stretched; adjectives raise a triumphant fist. Often, edging toward song or, with arms gesticulating, words carrying hope, pride, or disappointment may stop on a dime and—with a second breath—segue into something new.

Such movement characterizes You Bring Out the Laos in the House, from 2006, Catzie’s most celebrated poem to date. With a three-word gauntlet of “You bring out,” repeated and used to initiate each interlude, she scrutinizes how relating and interacting with others spur on self-examination (a process that is, invariably, filled with those aforementioned emotions): “You bring out my best features,” she begins. Then, successively, touching upon a mixture of misunderstanding, objectification, and alienation, different provoked responses add to the impending momentum: “You bring out the interpreter in me…You bring out the comparisons that bring out the authority in me…the impatience” and more (as this signature stem of words turns into a refrain, one that joins a descriptive mix of reflection, humor, and poetic bite).

Catzie (who is half of the spoken-word duo, Yellow Rage, as well as a solo performer) sees herself through a prism…one that doesn’t refract light but words—not easy words that one might glean from a dictionary or that spring forth, like Emily Dickinson’s, from the privacy of her bedroom. Instead, her words are ringed out of society at large—from you and me. They’re demanded, honed, and volleyed—in an amalgam of relational exchanges (what daily life itself has to offer) until they’re grabbed by her metaphorical hands, owned, repurposed, and performed into art: her art.

Born in a Thai refugee camp in 1980 but raised in Philadelphia, Catzie is Lao-American. That means two things. While she (like anyone who came of age, here, in the States) is undeniably American—speaking and thinking in English as fluidly as a skater might glide across a rink or comporting herself in a totality of mannerisms and believing in dreams that any American might also exhibit—she is, in addition, Lao. The proximity of her parents’ experience—one which is overwhelmingly defined by Laos—cannot help but bleed into hers as well, like how two cloths simultaneously wet from rain might find their colors intermingling.

But, of course, that reality can be complex. The part of her that’s American is as readily available as the music that she’s downloaded or the urge that prompts her to order a hamburger. But, the part of her that’s Lao isn’t as clear or near. It reaches back into a muddled time where shadows still lurk, to a land, overlooked by the general public, that’s remote and made even more foreign by its seeming obscurity. The fact that Laos is buried deeply under these inaccessible layers not only hides it from the American public (more ignorant of both geography and history than not) but, unfortunately and ironically, from the Lao people themselves—particularly the new generation of Laotians, raised in America, that don’t have first-hand memories of Laos and what happened there.

The Lao community in the U.S., for example, isn’t the Chinese or Vietnamese communities—in the sense that it’s much smaller and, as such, has a much reduced, more tenuous foothold in the American consciousness. These larger Asian communities, drawing upon its cultural resources—most notably its rich and varied cuisines—have only strengthened its place through food (something of the culture with which the broader society can find interest and which, over time, allows that food to slowly become a “normal” fixture).

In the case of the Chinese, for instance, its famed cuisine, which has become “Americanized” (and, by virtue of that, a part of the dominant culture itself) has helped root the Chinese to this country and make them more visibly a part of it—however superficial (with the proliferation of fried rice, General Tso’s Chicken, and pork buns) that process may be. It’s only a slight exaggeration to assert that every city and town in the U.S. has, at least, one Chinese restaurant. It’s, nonetheless, a fact that its food has given Chinese people, the largest Asian population in the U.S., an advantage that the Lao community just doesn’t have. The hegemony of Chinese food, for instance, is Goliath-like and dwarfs rivals; but, it serves to bring all things Chinese closer to the mainstream on its great coattails.

Immense traditions, like Chinese food or that great monolith that is American food, can, indeed, have that power to dwarf. In another part of her poem, Catzie says resolutely: “You bring out the part of me that says I don’t like rice.” To the audience, it could mean jasmine rice or Uncle Ben’s. Next, she asks quizzically: “But, how can I be Asian and not like rice? Then, she answers—to deny the irony: “It’s not so much that I don’t like rice, I just don’t like your rice. Because what we have, kow niew, sticky rice, is the sweet kind that we ball into our hands to eat while sitting on floors enjoying each other’s company…”

In another section, Catzie confesses that “You bring out the stink test” to offer a second point of food-related differentiation. No one, surely, would “bring out” such a test for duck sauce, egg rolls, or soup dumplings—or for ketchup, French fries, or tacos and salsa for that matter. “You bring out the stink test, the one where I make you smell the essence of ‘nam baa’ and ‘badaak,’ otherwise known as fish sauce and dirty fish sauce, so dirty that you can only find it in unmarked jars hidden underneath kitchen sinks…”

Growing up, Catzie did not and could not see the Lao part of her reflected in her surroundings: be it from below the kitchen sink or “above it.” Whereas other Asian groups, especially the Chinese, had a distinct neighborhood and storefronts to solidify their physical, economic, and, yes, cultural presence in Philadelphia and could be singled-out and celebrated during Asian heritage month or with the Chinese (lunar) New Year grabbing its fair share of annual attention, Catzie, like other Laotians, ended up wondering about her own place in the larger Asian-immigrant experience, about her own identity and history, which seemed oddly invisible. Apparently nobody, at least initially, was talking about cultural identity and history—even in the broader Lao community itself.

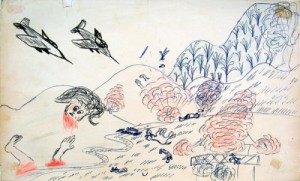

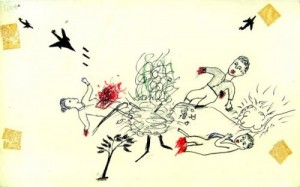

It was this circumstance and the subsequent inspiration that she gathered from watershed Lao projects—namely Thavisouk Phrasavath’s autobiographical film, Nerakhoon, which spotlighted the so-called Secret War in Laos during the Vietnam era and Channapha Khamvongsa’s Legacies of War, focusing on the U.S. bombing missions in Laos—that led Catzie, last year, to start her own project, Laos in the House (which she named for her poem). Her project’s noble goal is to explore the nexus of identity and history and to give voice, as Catzie’s poem did for her, to the Lao community so that its collective experience—in all of its undisclosed permutations (contained in the lives of ordinary folk)—can finally see the light of day and be documented. That untapped history, Catzie notes, is found in personal stories, which invariably draw upon memories of war, becoming refugees, and forging new lives.

The project, which will debut in Philadelphia in 2015 (at venues to be decided) is three-pronged. One component, which has been inaugurated in part—and, which will include accompanying workshops next year, entitled, The Stories Project, consists of creating an online archive of personal stories and narratives that Laotians, across countries and across generations, can submit via the Laos in the House website or through the Laos Diaspora Project worldwide. The second aspect, which is a collaborative effort with Legacies of War, will showcase drawings, writings, and videos that capture additional stories and narratives—alongside the famed Legacies of War drawings by Lao villagers, which depict, in haunting and brutal intimacy, the impact of the secret U.S. bombings in Laos during the Secret War there. These two components, in aggregate, will begin to fill in the gaping holes now present in the Lao and Lao-American story. While these two prongs will have an extended presence, the last one, a performance showcase, to include panel discussions as well—focusing on dance, music, fashion, and, undoubtedly, poetry—will take place over two nights next May.

Such an ambitious undertaking requires funding. And, so, that realization has led to the Laos in the House New Year’s Dinner next week on April 15th and 16th (an event that, yes, celebrates the upcoming Lao New Year—Songkran—but that will also, through its proceeds, aid the project as a whole). The event, to take place at Vientiane Café, Philadelphia’s foremost Lao restaurant, will feature eight authentic courses that’s not on the restaurant’s normal menu—highlighted by such items as “mieng kham,” a bite-sized lettuce wrap filled with dried fried sticky rice; “som sai gok,” Lao sour sausage, made from fermented pork mixed with traditional herbs; “som moo,” a kindred sour, fermented pork that’s pounded down and mixed with pig skin and garlic. Also, on the menu will be “thum bak hoong,” a Laotian version of papaya salad—funkier and more complex than its Thai counterpart due to the inclusion of fermented shrimp and crab pastes, and “gang na mai gup kai moat,” a string of words that translates to bamboo stew with ant eggs—a special dish that features bamboo, which looks familiar enough, but with ant eggs, as well, that resemble white Tic Tac mints.

The dinner, in all of its splendor and celebratory spirit, is, really, a de facto component of the Laos in the House Project too, and can be seen as a sort of quasi-fourth prong (although it’s not publicized as such). That’s because the New Year’s dinner will showcase Lao food and spotlight it and, in so doing, allow for more storytelling. How can it not? Food, embedded in daily life and customs, is as defining as any part of culture (such as language and identity). While there won’t be people drawing images of food or making video collages of it (or, maybe, there will be)—there, certainly, can be shared stories about it (as the Songkran dinner will undoubtedly evoke food memories): about a time and place, back in Laos where folks smelled the same smells, tasted the same flavors, when village life thrived, and when normalcy, seeming like an alien force once the bombs began to fall, still ruled. Or, maybe, food, like a life force, was something that made living bearable and grounded it to a routine that buffered the suffering that followed.

Catzie continues on: “You bring out the weird food references but still make me feel comfortable enough to talk about liking ant egg soup, fried grasshoppers, beef in blood sauce, and my favorite…fertilized chicken eggs.” The poem’s most uproarious moment (verified by the laughing that inevitably ensues) comes when, poking fun at herself and Lao tradition, Catzie offers the punch line—that these Lao foods would be at home on an episode of Fear Factor (where contestants were challenged to defy their fears and eat all manner of unspeakable things—presumably, Lao food included). Surely, we all understand the healing power of laughter; we know that; but, food—especially, that which deeply belongs to a people (and that reaches back into memory)—can offer healing too. Such is the unpledged but redeeming power of food.

Copyright 2014 (Corbo Eng). All rights reserved.

Photos by Corbo Eng (unless otherwise stated).