(by Corbo Eng)

Even if, hypothetically, for some reason, their renowned pit masters forgot how to prepare the barbecue that has made Smitty’s Market famous and began serving a substandard product, it would not matter; Smitty’s would still be a mandatory stop on any barbecue tour of Central Texas. It simply enjoys too much history and plays too central a role in local lore and in the imagination of those who hold barbecue dear to their hearts. At the very least, it is a living, working museum of the highest order—where one can witness how barbecue in Central Texas (particularly, in Lockhart, the acclaimed BBQ capital of the world) is supposed to be made and taste the end product for oneself. Yet, to call it a shrine, to tempt exaggeration, is not stretching the truth at all.

Upon entering, it is clear why this is the case. Customers are immediately swallowed up by a dark, narrow corridor. The dark reddish-brown tones of the walls and high ceiling fade into gray, then, black and might appear, casually, to be the consequence of a sinister paint job. But, upon close inspection, it becomes clear that the look is result of ash and soot that have accumulated over decades of smoking meat indoors. Indeed, it is an imposing physical space that seems, at first, more ominous than auspicious. Where one would expect to see hordes of people immediately gathered inside and diners in a din of revelry right past the front door, instead, is devoid of people. It is quiet…eerily so.

Halfway down the silent passageway, there are the old, dingy photographs of the proprietors (presumably of those who were part of the original Kreuz Market, the forerunner of Smitty’s). An odd assortment of fixtures and interior appointments and the dormant, retired brick pits at the end of the corridor and in the adjacent chamber (exuding age and character and, yes, caked with that same ash and soot) build off of that imposing first impression and provide an unused space where onlookers can gain a nascent understanding and appreciation of Smitty’s time-honored tradition and where their imagination can begin to find solid footing.

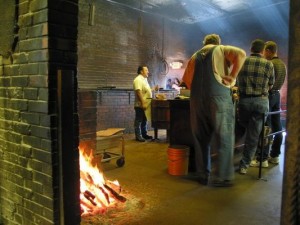

But, really, it is in the smoke room (where the working pits are and where customers place their orders) that really provides that footing—for once customers catch a glimpse of those pits (see the charred, worn charm of its brickwork), finally hear something other than themselves, smell the dense aroma wafting through the room, and see that roaring fire conjoined and embraced by eviscerated embers on the concrete floor next to them…all of this is as guttural and inspiring as anything. To suddenly stand before those pits (with slabs of ribs and hunks of brisket and links of sausage dangling therein), to understand that those meats have been smoking for upwards of twelve hours under the supervision of benevolent smoke and fire (as they always do), and to witness all of the assembled attendants and patrons is to literally stand at the altar of history (where some claim the barbecue gods themselves, over the years and at present, have anointed Smitty’s venerated smoke room with their own blood, sweat, and tears).

Indeed, it is quite a breathtaking experience to stand there in that room—and not just because it can routinely exceed 100 degrees. Of course, the menu boards are there; and, diners, if they have not already done so, should briefly review the choices and consider what to get; but, the real test of that room—with light, fire, and the dim walls pressing against each other, the real call from the gut—should be to simply stop and look around silently and respectfully (ignoring the fact that others are placing their orders) and soak in the ambiance of that space. And, a key part of that process—if not the core of it—is to feel the fire from the floor upon one’s tender face. If that means having to move in, to step forward, to move to the left or right; then, so be it. To feel that heat upon one’s cheek is to receive a loving kiss and to feel the very life-force of Smitty’s itself.

However, having engaged that force and having placed one’s order, taken the food, swaddled in butcher paper, on its tray out to the brightly lit dining hall that adjoins the smoke room is to step into a decidedly different space altogether. It can be a rather visceral jolt and transition, indeed. With diners eating their meal on long wooden rectangular tables and sitting in metal folding chairs, the scene is like something out of a Friday night social inside a church basement somewhere. Stepping into that dining hall from the smoke room, one literally goes from the sacred to the profane. Historians, documentarians, and hardcore barbecue aficionados would not necessarily bolt to it to investigate it. But, still, it is where, ultimately, one finally comes to eat the barbecue itself; and, due to that, the dining hall is a festive place filled with a happy, bright reverence.

Certainly, that was my frame of mind as I sat and devoured my order of brisket, sausage, and ribs (ripping the three meats with my hands, without the use of utensils or dabbing them with any accompanying sauce, as is customary) and consuming them along with the usual sides of saltine crackers and slices of white bread. Sure, my dining companions and I chitchatted between bites, compared impressions of the food, and exchanged a few pleasantries with some of the regulars; but, as well, there were stretches where I simply ate in silence—as if time had paused and my tongue had locked onto every morsel of flesh that I offered it.

Now, with the passage of time and being a couple of years removed from my visit there…in thinking about Smitty’s—and, in trying to extricate the hold of its physical presence and history from the final assessment of the food that I ate there—I find that it is like trying to remove a lasso that has wrapped around my body. With every attempt to squirm away, I only become more entangled and more prone to look upon Smitty’s through the filter of my eyes rather than stomach. That pronounced, majestic interior with its amber-brown hues (colors that Mark Rothko, a member of the Color Field school, would undoubtedly have cherished) and that stretch into a wash of black soot, linger in my mind and take me past the long corridor into the hallowed smoke room with its ancient, spiritual pits.

In contrast, my juxtaposed memory of the food—strained in its attempt to capture a meal that seems now to be, only, faintly outstanding at best—just drifts away ever so intangibly like puffs of lost smoke rising into a big expanse of Texas sky. Ultimately, I would love to go back…if for nothing else than to stand in that smoke room, at its altar—with that heat—one more time.

Copyright 2014 (Corbo Eng). All rights reserved.

All photos by Corbo Eng (unless otherwise stated).