(by Corbo Eng)

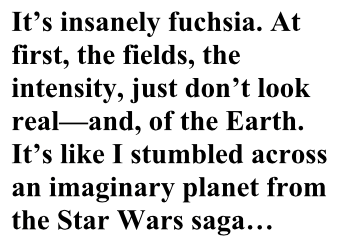

My knowledge of geography is pretty good; so, with Jeffrey Weiss mentioning “Pacific Grove” just now, I can see it—vaguely, in my head. I know that it’s on the same peninsula along the ocean, roughly at the mid-point of California’s coastline, with Monterey just to the east, Carmel to the south, and Big Sur somewhere nearby. And, I almost see it—Pacific Grove: a quaint town, no doubt, with manicured streets, store-lined sidewalks, and blue, foamy waters at its feet. But, I’ve never been there before; nor, have I seen any photos of it. Then, because of that—because it’s tenuous—it’s lost. The image is gone.

My knowledge of geography is pretty good; so, with Jeffrey Weiss mentioning “Pacific Grove” just now, I can see it—vaguely, in my head. I know that it’s on the same peninsula along the ocean, roughly at the mid-point of California’s coastline, with Monterey just to the east, Carmel to the south, and Big Sur somewhere nearby. And, I almost see it—Pacific Grove: a quaint town, no doubt, with manicured streets, store-lined sidewalks, and blue, foamy waters at its feet. But, I’ve never been there before; nor, have I seen any photos of it. Then, because of that—because it’s tenuous—it’s lost. The image is gone.

In that moment, I hear Jeffrey Weiss’s voice again, “I mean, I could throw a rock down the street; and, it would go into Monterey Bay. I have fishermen who call me from the water and tell me what they have.” I picture Weiss on his cell phone in his restaurant; and, I see a man standing erect on his fishing boat, holding a fish in his hand—gesturing as people do when they’re on the phone—and happily saying something that a chef, needing a fresh catch, might want to hear. There are rods, maybe nets (I’m not sure), and fish, wiggling, tangled with each other in a pile of fins and dampness. It’s like this that I see Jeffrey Weiss, under a cloudless sky, in his kitchen, inside his restaurant, in this idyllic place—cooking as he desires.

It’s a place, at least, from my perspective, that’s nowhere and somewhere all at once and so far away—not only from DC where I am, now, with Weiss—talking and eating cured meats at The Partisan, a restaurant, like Weiss, that’s known for charcuterie but, also, far from the country with whose food Weiss fell in love: Spain. Spain is as distant as the intervening land and separating ocean make it out to be despite the pervasive Spanish influence in California. Spain, actually, is quite near to Pacific Grove in that sense; but, I know I’m missing the point. Really, the distance is neither nearer nor farther. Weiss, who has traveled in Spain extensively, cooked there, and absorbed its food traditions, deals in something that can’t be measured in miles.

Spain is his culinary muse; and, like Rick Bayless has Mexico and Andy Ricker has Thailand, Weiss has Spain; and, it’s, frankly, as near as his own thoughts—where the food and his experiences there, posing in present time, inform his instincts and shape what’s on his menu, at Jeninni Kitchen and Wine Bar, in Pacific Grove—where he’s the executive chef. Customers may come for his famous paella, boasting saffron-scented rice laid out on a giant pan with shrimp that are almost the size of a man’s fist; but, it’s the elegant iterations of charcuterie—pâtés, rillettes, terrines, and sausages—that provide a glimpse into his soul.

——————————————————————————————————————————

Charcuterie, that branch of cooking that deals in forcemeat, is revered for the textures and complex flavors that characterize it. Pork, the meat of choice, is made spreadable, pressed into loafs, shoved into casings, and, with the resources of space and time—and revealing another facet—combined with salt and spices, cured, and frequently smoked until it is transformed into luscious, mouthwatering hams. Artistry, know-how, and patience come together. It’s artisan in a way that is real and time-honored.

Not surprisingly, it’s also French charcuterie that we, as Americans, know best—as the nomenclature and the very word, “charcuterie,” are, themselves, French. That circumstance is understandable given how French food and techniques so dominate in the West. Where there are any gaps, Italian salumi, which includes prosciutto and pancetta (among other familiar items), nudges out rivals and fills the holes without much complaint and fuss.

Not surprisingly, it’s also French charcuterie that we, as Americans, know best—as the nomenclature and the very word, “charcuterie,” are, themselves, French. That circumstance is understandable given how French food and techniques so dominate in the West. Where there are any gaps, Italian salumi, which includes prosciutto and pancetta (among other familiar items), nudges out rivals and fills the holes without much complaint and fuss.

The charcuterie of Spain, like a stepchild, is largely overlooked; and, that became all too apparent to Weiss when he worked as a line cook in New York, beginning in late 2010, at The Breslin, one of April Bloomfield’s restaurants—a sister spot to The Spotted Pig, Bloomfield’s Michelin-starred gastropub in the West Village. For a time, Weiss worked the overnight shift.

“There was a team of guys making the charcuterie,” Weiss recalls. “But, there was this one old Swiss guy who was the main one doing the terrines and stuff.” He impressed Weiss. “He knew his shit,” Weiss declares. But, when Weiss asked him about morcilla, a blood sausage that’s popular in Spain, the “old Swiss guy” drew an absolute blank. “What are you saying?” the old man retorted. Although Weiss doesn’t convey the man’s expression, I can see something hinting at consternation—as if he, with furrowed brows and pursed lips—felt that Weiss, an upstart line cook, was being deliberately challenging or obtuse. But, of course, Weiss wasn’t.

At that point, Spanish charcuterie, like a running commentary or an inescapable point of reference, had already gained prominence in Weiss’s mind; and, naturally, he simply wondered just how far this man’s knowledge of charcuterie extended and, later, why, ultimately, he knew nothing about the Spanish version of it.

At that point, Spanish charcuterie, like a running commentary or an inescapable point of reference, had already gained prominence in Weiss’s mind; and, naturally, he simply wondered just how far this man’s knowledge of charcuterie extended and, later, why, ultimately, he knew nothing about the Spanish version of it.

At The Breslin, there was a wall where cooking texts were shelved. Among the various titles, Weiss noticed Michael Ruhlman’s tome on charcuterie, regarded by many as the seminal book on the topic, and the Culinary Institute of America’s “Garde Manger” textbook, which focuses on food and recipes relating to the cold station—including pâtés and terrines. But, these books aren’t about Spanish charcuterie. “There’s no Spanish book,” Weiss, recalling his thoughts at the time, remembers. “I don’t think anyone’s ever written about this stuff.”

It was, then, with these books in mind and noticing the void, that Weiss had his “ah-ha” moment. He would write a book himself—a book about Spanish charcuterie. He did Google searches to see if any book had been published on the topic—to determine if his initial hunch was right. And, it was. There was nothing available in English and, incredibly, nothing in Spanish either. Weiss thought to himself, “Shit, I have a background in this stuff. I lived in Spain. I worked it. I saw it. I don’t know if anyone in America right now other than a Spaniard has seen what I’ve seen.” Having spent the previous year in Spain—traveling and cooking there on scholarship—it wasn’t hyperbole; it was true.

——————————————————————————————————————————

In 2009—in the months before leaving for Spain—Weiss was still a student at Cornell University’s School of Hotel Administration—a school with an Ivy League pedigree and a long and esteemed history. Despite the school’s name and it’s implied focus, he had enrolled at the Hotel School to continue his pursuit of the culinary arts, which he had started at Mission College, a 2-year institution, a few years earlier but, also, more importantly, to study restaurant entrepreneurship.

In 2009—in the months before leaving for Spain—Weiss was still a student at Cornell University’s School of Hotel Administration—a school with an Ivy League pedigree and a long and esteemed history. Despite the school’s name and it’s implied focus, he had enrolled at the Hotel School to continue his pursuit of the culinary arts, which he had started at Mission College, a 2-year institution, a few years earlier but, also, more importantly, to study restaurant entrepreneurship.

It was then, at a time when he had, essentially, a semester left before graduating, that he learned of a scholarship program, called the “The Training Program in Spanish Gastronomy,” that allows young people to travel to Spain, learn about the cuisine, and work as a culinary intern at some of the most acclaimed Spanish restaurants. The scholarship, which is offered under the auspices of the Spanish Institute of Foreign Trade or ICEX (Instituto Español de Comercio Exterior), was, at the time of Weiss’s participation, for a full year and was, from Weiss’s perspective—as one who was intensely interested in Spain and its food—an opportunity of a lifetime.

Of course, there was the matter of applying for the scholarship in the first place. It accepted applicants internationally and was highly competitive. “There were over a hundred American applications alone that year,” Weiss says. Looking back, Weiss had concluded, if not a bit modestly, that his chances were slim because his cooking background was, in his estimation, not strong enough. “There were a lot of really talented guys,” Weiss explains. His good friend, Paras Shah, an ICEX scholarship winner during that same award cycle and who joined Weiss in Spain, was a chef at Momofuku Noodle Bar and had worked with Jonathan Benno at Per Se. No one would argue that Shah’s credentials weren’t impressive; but, Weiss’s résumé wasn’t anything to sneeze at either. He had a trump card in the form of José Andrés.

Weiss had worked at Jaleo, Andrés’s famed tapas bar in Washington, DC while he was enrolled at Cornell—having secured a position there through Hollis Silverman, the director of restaurants and hospitality at Andrés’s ThinkFoodGroup. One of Weiss’s professors contacted Silverman after Weiss had expressed a desire to work for Andrés. Given Weiss’s interest in Spanish cuisine, the hook up was a no-brainer.

Weiss had worked at Jaleo, Andrés’s famed tapas bar in Washington, DC while he was enrolled at Cornell—having secured a position there through Hollis Silverman, the director of restaurants and hospitality at Andrés’s ThinkFoodGroup. One of Weiss’s professors contacted Silverman after Weiss had expressed a desire to work for Andrés. Given Weiss’s interest in Spanish cuisine, the hook up was a no-brainer.

Weiss, eventually, worked in DC at Jaleo for several months, in the premiere Spanish kitchen for the preeminent Spanish chef in the United States, won friends, and formed bonds—including a bond with Andrés himself. “One day, I was cleaning artichokes,” says Weiss. “And, I hear this booming voice: ‘Hola, amigo!’ It’s José Andrés. So, I talked with him for a while.” Andrés, according to Weiss, is very much the big personality that he famously appears to be.

As the head of the ThinkFoodGroup, with a restaurant empire to run, and a full schedule of conferences, speaking engagements, and public appearances taking him to and fro, Andrés couldn’t have been around his DC restaurants all that much—but, at least, enough to catch Weiss on that one memorable occasion in Jaleo’s kitchen. But, it wasn’t for Weiss, what was most memorable apparently. “There’s a funny story,” Weiss confesses. “He actually had me go out to his house. I cooked at his house.”

With this admission, I wonder if Andrés, wanting to put his young cook through his paces, had called Weiss out to his house to test him—to see for himself what Weiss could do. Maybe, what’s funny was Weiss kicking some serious ass and cooking up a storm in the kitchen with Andrés looking on—with a big approving smile that was the size of Spain on the famed chef’s face. Or, maybe, but, hopefully, not—that by “funny”—Weiss is really suggesting that there was a mishap of some sort with hilarity ensuing. Perhaps, Weiss had taken a spatula and flipped an omelette onto Andrés’s head.

Weiss, answering me, says. “It wasn’t an audition. He was having a party.” Weiss, then, explains the funny part. “Andrés let me drive his car.” I don’t expect to hear that. “He had gotten a bunch of stuff for us to cook. And, then, he says, ‘Oh, no, I forgot the brioche.’” But, apparently, as the host, Andrés was indisposed and couldn’t leave. As Weiss remembers it, Andrés gave him some money to buy the brioche—a hundred bucks, which was a ridiculous amount and ten times what was needed—and told Weiss to run the errand for him. “Take my car,” Andrés said. “You go this way and this way, left, right, left, right; and, you get to the store…here’s my keys.” Hearing Weiss relay the episode, I see that Weiss is enjoying himself, that it’s “funny” in the good sense; and, I can see Andrés, in his bombastic style, doing and saying just that—almost as a caricature of himself in a Saturday Night Live skit.

Weiss, answering me, says. “It wasn’t an audition. He was having a party.” Weiss, then, explains the funny part. “Andrés let me drive his car.” I don’t expect to hear that. “He had gotten a bunch of stuff for us to cook. And, then, he says, ‘Oh, no, I forgot the brioche.’” But, apparently, as the host, Andrés was indisposed and couldn’t leave. As Weiss remembers it, Andrés gave him some money to buy the brioche—a hundred bucks, which was a ridiculous amount and ten times what was needed—and told Weiss to run the errand for him. “Take my car,” Andrés said. “You go this way and this way, left, right, left, right; and, you get to the store…here’s my keys.” Hearing Weiss relay the episode, I see that Weiss is enjoying himself, that it’s “funny” in the good sense; and, I can see Andrés, in his bombastic style, doing and saying just that—almost as a caricature of himself in a Saturday Night Live skit.

Weiss continues, “And, I get into José Andrés’s car and I take a photo, of course, because I’m in José Andrés’s car. And, I turn it on; there’s no gas…like, it’s on E.” Weiss hesitated and wondered whether or not he should go. He didn’t want to get stuck somewhere and have to sheepishly call Andrés for help—or, as I fear, be forced to stand on the side of the road and flag down a police car, all the while with a “hundred dollar” loaf of brioche in the front seat. But, for me, it was clear. Chances are Andrés, welcoming a laugh and an opportunity to help yet again, wouldn’t have minded getting that call.

Ultimately, Weiss did call Andrés for help after all—but, under much different circumstances. When it came time to apply for the ICEX scholarship—and with that year in Spain weighing on his mind, Weiss contacted Andrés’s ThinkFoodGroup. “So, I called up José’s HR people and asked if they could write me a letter of recommendation. They said they would, and I didn’t worry too much about it.” But, Andrés had taken matters into his own hands. Weiss still can’t believe it.

“I didn’t find out until later that Jose had picked up the phone and called Spain and said, ‘Take that guy.’ I was one of two Americans who got in that year. There were only twelve of us from around the world that won it, and I was one of them because of José.” Weiss stops for a second and ponders the enormity of Andrés’s gesture. “If José didn’t make that phone call, I wouldn’t have been accepted. I wouldn’t have gone to Spain to see what I did. I wouldn’t have written a book. I wouldn’t be sitting where I am today. I owe him a lot.”

——————————————————————————————————————————

Weiss tells me that he owes Steve Chan a lot too. I hear him, but it doesn’t register. I’m distracted momentarily by our waiter who brings Weiss the bourbon he’s ordered and fills my glass with water for what seems like the twelfth time. But, really, it isn’t so much that I’m reaching for my glass again to take an obligatory sip—to justify its being there and having just been filled so dutifully—it’s that the name catches me flat-footed.

Weiss tells me that he owes Steve Chan a lot too. I hear him, but it doesn’t register. I’m distracted momentarily by our waiter who brings Weiss the bourbon he’s ordered and fills my glass with water for what seems like the twelfth time. But, really, it isn’t so much that I’m reaching for my glass again to take an obligatory sip—to justify its being there and having just been filled so dutifully—it’s that the name catches me flat-footed.

When I hear, “Steve Chan,” it doesn’t mean anything to me. I can’t place the name or think of a restaurant to go with it. “Who is he?” I ask myself as I rummage through my mental file of chefs. The name sounds like some kind of generic placeholder—like the Chinese version of “John Doe” that might be used when a Chinese guy gets run over by a bus and can’t be identified because he’s not carrying I.D. The newspaper headline would read, “Unidentified Steve Chan Dies in Tragic Bus Accident.”

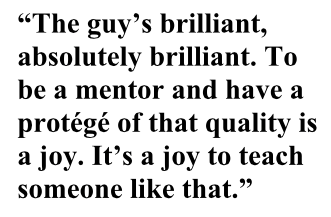

But, as it turns out, Steve Chan, of course, is very much a real man—and, yes, a chef—at a place called, Fremont Hills Country Club; but, when Weiss met him, worked for him, and when Chan shook up Weiss’s world, Chan was the executive chef at Lion & Compass, a restaurant in Sunnyvale, California near where Weiss grew up and attended college.

But, as it turns out, Steve Chan, of course, is very much a real man—and, yes, a chef—at a place called, Fremont Hills Country Club; but, when Weiss met him, worked for him, and when Chan shook up Weiss’s world, Chan was the executive chef at Lion & Compass, a restaurant in Sunnyvale, California near where Weiss grew up and attended college.

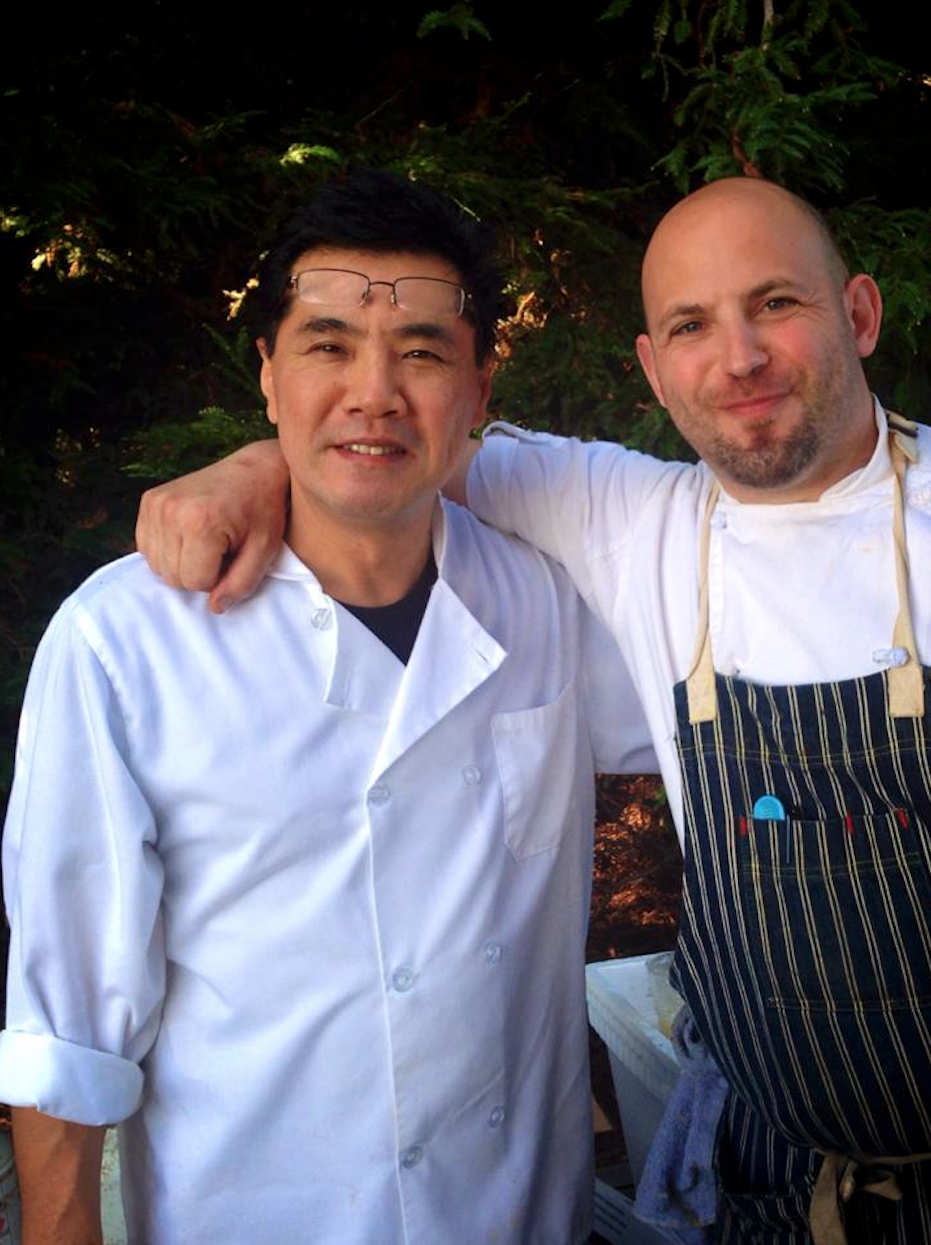

“He and Martin Yan (of Yan Can Cook fame) were contemporaries; they worked together,” Weiss explains.“They were the original pan-Asian fusion type guys.” The mention of Martin Yan, suddenly, and Weiss’s linking him to Chan only makes me speculate more on why I hadn’t heard of Chan before. I think, “He must be of some stature.” Weiss talks up Chan for a few minutes and, in doing so, refers to him as “my mentor” on multiple occasions. There’s an enthusiasm in Weiss’s voice and a palpable respect as he’s sharing vignettes and recalling private interactions.

“That’s how Steve Chan trained me.” The sentence jumps out from a string of words—with nouns, verbs, and superlatives rolling off of Weiss’s lips. I nod assertively as if to say, “Oh, okay…that Steve Chan;” but, I don’t really know—not until later, as I’m intrigued by this man’s role in Weiss’s life, and am moved enough to call Chan to find out for myself.

I catch Chan at Fremont Hills as he’s winding down from his day. “Corbo,” he says with a warm, enthusiastic voice. “Is that you?” He says it like we’re old buddies and not because I had told him I’d be calling him then. Although I’m interested in finding out who he is and something about his career, he’s more interested in talking about Weiss. And, he needs little if any prompting.

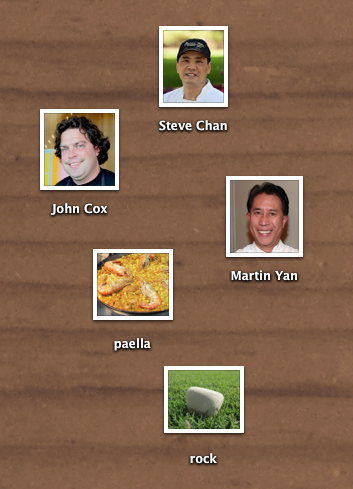

“Oh, that Jeffery! I mean, it’s like I’m his high school football coach; and, it’s like seeing one of my star players go to the Super Bowl. I’m just happy to be along for the ride, to witness it all. The guy’s brilliant, absolutely brilliant. To be a mentor and have a protégé of that quality is a joy. It’s a joy to teach someone like that.” Chan is effusive. It’s like Chan had had a long, hard day and the opportunity to talk about Weiss has opened up the floodgates.

“Oh, that Jeffery! I mean, it’s like I’m his high school football coach; and, it’s like seeing one of my star players go to the Super Bowl. I’m just happy to be along for the ride, to witness it all. The guy’s brilliant, absolutely brilliant. To be a mentor and have a protégé of that quality is a joy. It’s a joy to teach someone like that.” Chan is effusive. It’s like Chan had had a long, hard day and the opportunity to talk about Weiss has opened up the floodgates.

“He got to work in some of the top restaurants in Spain, in the world really, working with some of the top chefs around,” Chan continues. “And, he still calls me every so often and thanks me. I say, ‘Jesus Christ! Save that little ink.’ He thanks me when he gets interviewed. He talks about me in interviews. ‘Stop this. Use that little bit of ink for yourself.’ But, the man is genuine. He’s genuine.”

I have to rely on Weiss to fill in the back story. “Steve grew up on the streets of San Francisco,” Weiss tells me before my calling Chan. “He ran with the old gangs in Chinatown back in the 60s and 70s. He was a punk off the streets. His brother, who was a chef too, got Steve into the ACF (American Culinary Federation) program out of the Community College of San Francisco.” Weiss goes on to weave a tale, a rescue story of sorts of how Chan, post-ACF, eventually landed at “one of the grand kitchens back in the day where there were multiple chefs de partie, garde mangers, butchers, specialists, the whole thing.” There, as fate would have it, Chan found a mentor—someone Weiss describes as an “old Swiss guy.”

I immediately notice that it’s the same tag that Weiss gave the master terrine maker who had so impressed him back at The Breslin in New York, the old man who ended up not knowing anything about Spanish charcuterie when questioned. “There are a lot of old Swiss guys kicking ass in restaurant kitchens,” I think to myself. Apparently, this one whipped Chan into shape.

When I finally get Chan to speak about himself, he doesn’t mince words. “I’m from the old school,” he tells me ardently. “That means a chef leading his troops. A chef might say, ‘Move faster.’ Then, a chef has to be able to show them. The chef has to be the most highly skilled guy in the kitchen—the fastest, the smartest. That’s what he has to be in order to lead his troops.”

Chan elaborates more, which leads into remarks about motivating his cooks and, most crucially, how they should be treated. “As a cook, you’re making $15 – $16 per hour, which is peanuts. It’s hard work, you know. A lot of chefs don’t give a crap. If a cook can’t do the job, the chef says, ‘Alright, I’ll go find someone else.’ I mean, your people are your assets. Every general is still a soldier. A chef is still a cook. Every cook contributes. The dishwasher has to be proud of what he does. You have to instill that.”

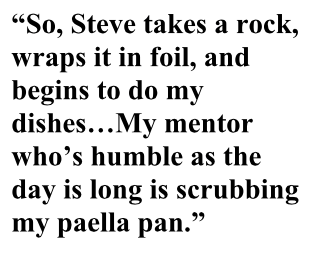

Weiss, who met up with Chan not long ago, tells me about that day. Upon hearing it, it strikes me as a story of Chan’s kindness and generosity. But, the story takes on a much larger meaning after speaking with Chan and absorbing his remark about a dishwasher being proud of his work. “I was doing a paella cooking demonstration,” Weiss says, beginning his account of what happened. “It was at this big, beautiful hotel out in Big Sur with John Cox, the chef there. We’re doing this big food and wine thing; and, I’m making paella overlooking the ocean. I invited Steve to hang out.”

Weiss, who met up with Chan not long ago, tells me about that day. Upon hearing it, it strikes me as a story of Chan’s kindness and generosity. But, the story takes on a much larger meaning after speaking with Chan and absorbing his remark about a dishwasher being proud of his work. “I was doing a paella cooking demonstration,” Weiss says, beginning his account of what happened. “It was at this big, beautiful hotel out in Big Sur with John Cox, the chef there. We’re doing this big food and wine thing; and, I’m making paella overlooking the ocean. I invited Steve to hang out.”

Weiss, who had learned how to make paella in Alicante, Spain—at a renowned restaurant famous for it—had never doubted his own handiwork. But, Chan, noticing that it was just slightly off, whispered a tip into Weiss’s ear—on how to improve it, something about the broth. “It turned out even better. He was absolutely right because he knows. And, he’s Steve.”

With the paella done and Weiss busy mingling with the guests, Chan began washing and cleaning up. “There’s no dishwashing station,” Weiss explains. “So, Steve takes a rock, wraps it in tin foil, and begins to do my dishes. My mentor…” Weiss stops mid-sentence. There’s incredulity in his voice. “My mentor who’s humble as the day is long is scrubbing my paella pan.” Weiss looks at me. It’s a look that suggests thankfulness, amazement, and a bunch of assorted feelings in between.

Chan’s version is a bit more matter-of-fact. “Yeah, I thought it was pretty clever. We literally had no soap and water. It was a paella pan which is pretty gritty and very seasoned. So, I take this rock and foil and try it. He needed his pan washed; so, I washed it. No big deal.”

Chan was probably crouching, scrubbing the big, shallow paella pan—going around and around that thing, a 16 inch pan, scrubbing away to get off the stuck on rice and charred bits. “The guy’s so humble,” Weiss says flatly and resolutely to conclude the story. “I hope, one day, to be like that.”

——————————————————————————————————————————

José Andrés was a mover and shaker even during Weiss’s time in DC and, already, a figurehead—a chef turned famous restaurateur and cultural icon who, seemingly, wielded more clout and influence outside of the kitchen as a businessman. Although he hadn’t yet expanded to Las Vegas or South Beach yet, Andrés was already a successful empire builder who had made DC’s Penn Quarter neighborhood unofficially his.

José Andrés was a mover and shaker even during Weiss’s time in DC and, already, a figurehead—a chef turned famous restaurateur and cultural icon who, seemingly, wielded more clout and influence outside of the kitchen as a businessman. Although he hadn’t yet expanded to Las Vegas or South Beach yet, Andrés was already a successful empire builder who had made DC’s Penn Quarter neighborhood unofficially his.

In addition to Jaleo, which was located on 7th Street, Andrés had opened Oyamel, which served modern Mexican fare, a couple of blocks to the south. Zaytinya, serving Mediterranean-inspired small plates behind a great modern edifice, occupied the corner at 9th and G Streets across the street from the main library. Minibar—his famous crown jewel, known for its exclusive six seat counter and impossible to get reservations—was, then, before relocating, just around the corner from Jaleo and Oyamel on 8th Street in a building that also housed the now shuttered Café Atlántico, Andrés’s showcase for “Nuevo Latino” cuisine.

Katsuya Fukushima, the chef and owner of Daikaya, the popular ramen bar and izakaya in DC’s Chinatown, had been part of that empire building as Andrés’s right hand man by helping him open all of his DC restaurants. Originally from Hawaii, Fukushima was essentially a local product—having studied at the University of Maryland and L’Academie de Cuisine in suburban College Park and Gaithersburg respectively. He rose up the ranks in the DC dining scene and gained a reputation for his talent and technical wizardry before Andrés snatched him up.

Fukushima, somehow, had even spent time, before working for Andrés, at elBulli (where Andrés, also, before him, had cooked) under Ferran Adrià, the greatest of Spanish chefs and the so-called “father of molecular gastronomy.” There, Fukushima honed his already prodigious skills and, in that laboratory of a kitchen, gained even more as elBulli’s secrets ultimately became part of his own body of knowledge—one that served him well in his full-time gig as the chef de cuisine at Café Atlántico and Minibar.

Fukushima, somehow, had even spent time, before working for Andrés, at elBulli (where Andrés, also, before him, had cooked) under Ferran Adrià, the greatest of Spanish chefs and the so-called “father of molecular gastronomy.” There, Fukushima honed his already prodigious skills and, in that laboratory of a kitchen, gained even more as elBulli’s secrets ultimately became part of his own body of knowledge—one that served him well in his full-time gig as the chef de cuisine at Café Atlántico and Minibar.

As an up-and-comer, toiling away at Jaleo, and ever aware that he was very much a chef-in-training, Weiss, undoubtedly, admired Fukushima. The two men, I assume, are near in age; but, I’m not sure. It’s just that Weiss’s tone is just so—that I get this feeling that he saw Fukushima as a role model of sorts, that Weiss wanted to emulate him, like a younger brother might an older brother or, in my mind, like how I’d regard a freelance writer who’s been published in the best food magazines and who can turn a phrase as easily as chewing gum.

“Katsuya was at Minibar. He was José’s R and D guy. He was such a rock star. I have so much respect for that man. I just wanted to learn, and he let me learn.” In that effort, Weiss made a frequent point of visiting Fukushima in his kitchen to glean whatever he could from him.

In fact, before meeting with me, Weiss tells me that he had actually gone to see Fukushima, earlier, in the afternoon, at his restaurant, Daikaya, to enjoy a bowl of ramen—not a bad choice on a cold, blustery day like today—and, to reminisce. “You know,” he says in a slightly lowered voice—as if anyone is going to overhear him. “Katsuya, his broth, for his different ramens, uses the master stock technique. So, his broth is over two years old, you know. It was very good today.”

In fact, before meeting with me, Weiss tells me that he had actually gone to see Fukushima, earlier, in the afternoon, at his restaurant, Daikaya, to enjoy a bowl of ramen—not a bad choice on a cold, blustery day like today—and, to reminisce. “You know,” he says in a slightly lowered voice—as if anyone is going to overhear him. “Katsuya, his broth, for his different ramens, uses the master stock technique. So, his broth is over two years old, you know. It was very good today.”

Then, Weiss and I have a brief exchange where he brings up the current bone broth craze and how he’s serving something like bone broth at his restaurant, Jeninni—but not as a hollow nod to a fad but because, as he explains it, it’s part of Spanish tradition. “It’s called caldo. If you walk around the North of Spain in the mountain towns where it’s cold right now, there are signs out in front of these places…chalkboards that read, ‘Hay, Caldo,’ which means ‘there is broth today.’ The tradition is that, when it’s cold outside and you want to warm up, you don’t get liquor.”

Weiss and I talk about bone broth and ramen for a few more minutes—the alchemy of the conversation making want to go straight home and concoct a witch’s brew. But, then, Weiss gathers himself and picks up where he left off. “I would be at Jaleo to do my eight hour shift and then, on my time, I’d go around the corner to Minibar…well, actually, I’d go work at Atlántico because Katsuya didn’t trust me at Minibar. I’ll do whatever you need,” Weiss remembers saying to him. “I’ll clean fucking mushrooms, whatever.” And, Fukushima, recognizing Weiss’s pluck and determination, allowed him to do just that. “I spent a lot of time there.”

——————————————————————————————————————————

In the fall of 2009, when Weiss was bound for Spain to begin his scholarship program, he had already mapped out his plan. No doubt thinking of Fukushima and his exploits at Minibar, Weiss wanted to intern and cook at elBulli. Who wouldn’t have wanted to do that? Ferran Adrià’s reputation in culinary circles was legendary; and, the allure of tweezers and foam and food as modern as modern can be would have wooed most aspiring chefs.

In the fall of 2009, when Weiss was bound for Spain to begin his scholarship program, he had already mapped out his plan. No doubt thinking of Fukushima and his exploits at Minibar, Weiss wanted to intern and cook at elBulli. Who wouldn’t have wanted to do that? Ferran Adrià’s reputation in culinary circles was legendary; and, the allure of tweezers and foam and food as modern as modern can be would have wooed most aspiring chefs.

But, Andrés talked Weiss out of it but not for reasons most of us would assume, that of saving an ambitious cook from the excesses of something too advanced—like a father might convince his young son to put on training wheels first before riding off unassisted. Rather, Andrés’s argued that Weiss would get lost in the shuffle in a crowded kitchen. “Well, you’re going to be one of sixty guys over there,” Andrés warned. “Look, go to Dani García. Dani García is the king of liquid nitrogen. He’s the next Ferran.”

Prior to winning his scholarship, Weiss had already visited Spain because his sister had studied abroad, gotten married, and settled in Spain permanently. On a trip out there to visit her, Weiss had dined at Restaurant Adolfo, Adolfo Muñoz’s outpost in Toledo where he met Muñoz’s son, Javier, and his daughter, Veronica. And, it was that connection that lingered and that drew Weiss to Muñoz when it came time to select which restaurants would become part of his scholarship year. So, in the end, Weiss choose to work with Dani García and Adolfo Muñoz.

Prior to winning his scholarship, Weiss had already visited Spain because his sister had studied abroad, gotten married, and settled in Spain permanently. On a trip out there to visit her, Weiss had dined at Restaurant Adolfo, Adolfo Muñoz’s outpost in Toledo where he met Muñoz’s son, Javier, and his daughter, Veronica. And, it was that connection that lingered and that drew Weiss to Muñoz when it came time to select which restaurants would become part of his scholarship year. So, in the end, Weiss choose to work with Dani García and Adolfo Muñoz.

Of course, Weiss had the best of both worlds. Muñoz is a product of Spain’s La Mancha region where the cooking is more rustic and rooted to a people and place. “Toledo is Don Quixote,” Weiss explains to me, referencing the famous literary Man of La Mancha. “The Spanish kind of regard La Mancha as the New Jersey of Spain. They look down on it a little bit. But, it doesn’t get more classic than Quixote. And, that’s the food of the poor. It’s the poorest of the poor out there back in the day. So, the tradition of that was something I wanted to see.”

On that basis, Weiss decided to go to Toledo first to work with Muñoz where he would likely encounter hearty stews and braises—with homely ingredients like olives, thyme, tomatoes, bread, potatoes, and lamb shoulder doing the heavy lifting. He knew afterwards, that he’d have a fundamental understanding of Spanish cooking as a result, which would ground him once he moved on to Calima, Dani García’s restaurant in Marbella.

There, it would be less about grounding oneself in tradition but, rather, pushing the culinary envelope further. Working under “the king of liquid nitrogen,” as Jose Andrés had called García, would mean, Weiss, immersing himself in “molecular gastronomy,” a style of cooking whose label seems to have been coined specifically for Ferran Adrià and Dani García and the modernist cuisine that they represent and helped make famous.

It would mean freezing all manner of edible things to chase freakishly new creations—making sorbet from wine, for example, or depositing puréed vegetables into a vat of that liquid magic, watching the frozen vapors rising up from the elixir, and reaching in to pull out something exhibiting a dramatically changed texture. It would be like going off to science camp where all the experiments would involve food in some way.

——————————————————————————————————————————

——————————————————————————————————————————

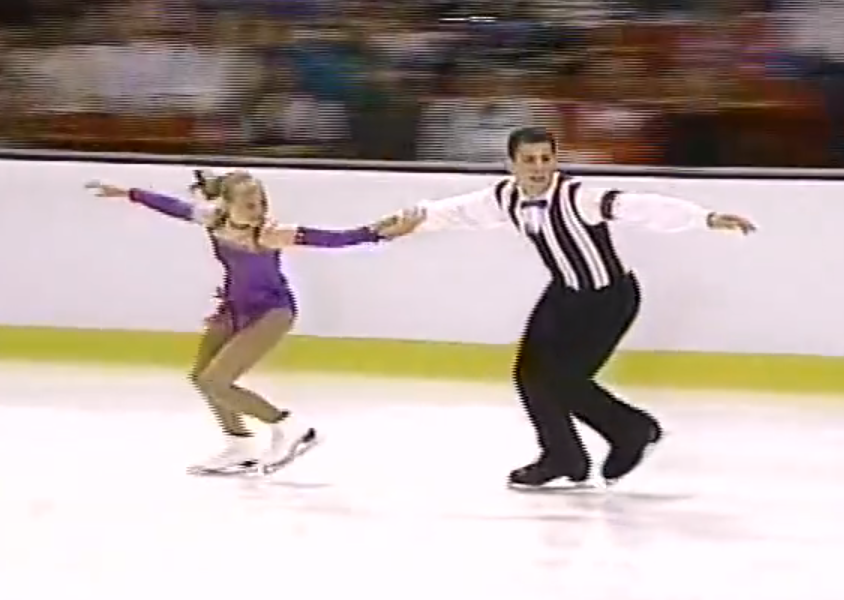

Growing up in Foster City, California—in the Bay Area between San Francisco and San Jose—Weiss knew nothing of liquid nitrogen, of course. I don’t think even Ferran Adrià with a crystal ball at his disposal had in those days. But, Weiss knew a thing or two about frozen vapors. He’d seen them, not in a kitchen, but, on an ice rink and, undoubtedly, on countless occasions. Before food and becoming a chef had taken over his life, Weiss was an elite pair skater, one who competed at the U.S. Figure Skating Championships. In 1996, with partner, Erin Elbe, he had won a silver medal.

Growing up in Foster City, California—in the Bay Area between San Francisco and San Jose—Weiss knew nothing of liquid nitrogen, of course. I don’t think even Ferran Adrià with a crystal ball at his disposal had in those days. But, Weiss knew a thing or two about frozen vapors. He’d seen them, not in a kitchen, but, on an ice rink and, undoubtedly, on countless occasions. Before food and becoming a chef had taken over his life, Weiss was an elite pair skater, one who competed at the U.S. Figure Skating Championships. In 1996, with partner, Erin Elbe, he had won a silver medal.

Not being an avid fan of the sport—particularly, in the mid-90s and early 2000s when I was following professional football or even, more likely, the U.S. bobsled team—I had known nothing of Jeffrey Weiss, the pair figure skater and had only heard of this part of his past in a tangential way once I had learned of him as a chef. I remember being, frankly, surprised at first.

Chefs, of course, don’t emerge fully formed. Like with any profession, the road from point A to point B can be circuitous and unpredictable. I had thought that going from figure skater to chef, at face value at least, was a big leap between two seemingly unrelated pursuits. But, really—looking closely at it—there’s physicality to being a chef that, at least, mimics being an athlete. There’s the need for exertion, stamina, and strength: the traits of an athlete. Weiss is a stout man—noticeably big boned, muscular, and, inarguably, strong.

“I did pairs,” states Weiss clearly. His calm, matter-of-fact tone does its best to take the apparent disconnection away. “I enjoyed being in a team environment where it wasn’t just me having to do something. I had to communicate with my skating partner and come together to figure out how to do x, y, and z. That was cool. I liked that.” When I probe further, Weiss emphatically reiterates that he had had no interest in skating individually. That wasn’t what appealed to him. “I like being part of a team, and it equates to what I do today.”

“I did pairs,” states Weiss clearly. His calm, matter-of-fact tone does its best to take the apparent disconnection away. “I enjoyed being in a team environment where it wasn’t just me having to do something. I had to communicate with my skating partner and come together to figure out how to do x, y, and z. That was cool. I liked that.” When I probe further, Weiss emphatically reiterates that he had had no interest in skating individually. That wasn’t what appealed to him. “I like being part of a team, and it equates to what I do today.”

“I work really well with Thamin,” Weiss says, referring to his business partner, Thamin Saleh, the owner at Jeninni Kitchen and Wine Bar. “We’re a team together. He runs the front. I run the back. He has a strong accounting background. I don’t love accounting. He has incredible wine knowledge…more than I will ever have and ever want to have. He’s very gregarious, a front of house specialist. He knows how to handle tables, how to handle guests. I love the food side. I know a lot about the food side. I don’t know everything; but, I know a lot.” Weiss almost runs out of breath but adds the clincher, “He’s exceptionally good at all the things that I’m not good at.”

Now, hearing him speak about the appeal of teamwork, the picture begins to fill in; and, I realize how Weiss sees the connection between skating and being a chef. But, also, I sense that something else, besides enjoying teamwork, like sheer determination or immense skill, is at play as well—that no one could possibly be successful as a figure skater (or a chef) without one of those forces. “You were pretty damn good.” I say assertively. Without hesitation, Weiss answers back, “I was pretty damn stubborn. I goofed off way too much. You always had to go chase me down in order for me to practice.”

But, as we talk further, I see Weiss’s self deprecation for what it is. Behind his supposed “goofing off,” there really was something pushing him as well—like that undeniable edge beneath a comedian’s humorous façade. “The Olympics were something you wanted, right?” I ask. Weiss makes it clear. “The Olympics? Hell, yeah. I mean, that’s what we work for. All that. It’s a goal to be achieved if you can. But, what percentage of skaters or any athlete in any sport gets to do the Olympics? It’s tiny. But, you do it because you enjoy it and because you’re good at it. You do it because it’s partly your job. I mean, there were days when I enjoyed it a lot less than others, you know. But, it was something that I knew I was good at and wanted to see how far I could take it.”

And, being true to himself, Weiss took it as far as he could. “Well, at one point, I had broken up with one skating partner. And, I was training a little bit on my own. Then, I was ready to find a new pair partner.” It was serendipitous that a female skater in L.A., named Rhea Sy, had just recently broken up with her partner as well. Mutually looking for new pair partners, Weiss met Sy. If there had been any doubt about whether or not she had what it took, Weiss resolved that question in his mind rather quickly. “She was good,” Weiss says. “GOOD,” he repeats boldly, leaving no doubt about her talent. “On a scale of one to ten, she was a twelve.”

And, being true to himself, Weiss took it as far as he could. “Well, at one point, I had broken up with one skating partner. And, I was training a little bit on my own. Then, I was ready to find a new pair partner.” It was serendipitous that a female skater in L.A., named Rhea Sy, had just recently broken up with her partner as well. Mutually looking for new pair partners, Weiss met Sy. If there had been any doubt about whether or not she had what it took, Weiss resolved that question in his mind rather quickly. “She was good,” Weiss says. “GOOD,” he repeats boldly, leaving no doubt about her talent. “On a scale of one to ten, she was a twelve.”

What so impressed Weiss was that Sy was able to complete a triple throw salchow—an unheard of feat, given the context. He stresses this fact with me, explaining it in terms a non-skater would understand. “We did a single…no problem, then, a double. Then, she said, ‘I’m ready to do a triple.’ You NEVER do a triple on the first day of a tryout. But, we did it; and, she landed. I was like, ‘Holy, shit!’ This girl is ridiculous and awesome and brave and strong. She’s everything you want.”

It was a find that one would assume had propelled Weiss to new heights in his skating career—to finally have such a partner. It’s the kind of seminal moment that would have illustrated all that stuff about teamwork that he elaborated on and that, if it were embedded in a book, would have tempted a reader to flip ahead to see what sort of athletic brilliance or sporting glory had taken place in the ensuing months and years ahead. But, in that encounter—to borrow a metaphor from another sport—life had thrown Weiss a curveball. He hadn’t met someone who would accompany him into the future—to further help write his story. Instead, he had met someone who would help him close this chapter of his life.

“After we finished, we said our goodbyes; and, I went to this little local restaurant to eat. I sat down, looked out the window, and said to myself, ‘I don’t want to do this.’ I had found the most perfect pair partner. This girl is everything. But, I don’t want to do this.” At the restaurant, Weiss called Sy to explain to her, as best as he could, what he had decided—that his heart wasn’t in it anymore and that her being “so fucking good,” as Weiss puts it, had made him see that. Sy understood. I understand too.

Weiss shakes his head, takes a sip of his bourbon, and says, “I didn’t want to waste her time.” I see it as true. But, also, I see that Weiss didn’t want to waste his time either—with the arduous training that’s certainly needed and always having to reach deep within to extract every last drop of motivation. Then, as Weiss confesses to me even further, there was the prospect of becoming what ice skaters, whose competitive and amateur careers have ended, eventually become if they join the professional ranks. It’s the touring and performances.

Weiss shakes his head, takes a sip of his bourbon, and says, “I didn’t want to waste her time.” I see it as true. But, also, I see that Weiss didn’t want to waste his time either—with the arduous training that’s certainly needed and always having to reach deep within to extract every last drop of motivation. Then, as Weiss confesses to me even further, there was the prospect of becoming what ice skaters, whose competitive and amateur careers have ended, eventually become if they join the professional ranks. It’s the touring and performances.

It’s the mentioning of this that triggers a memory for me, suddenly, of seeing on TV, somewhere, famous skaters like Nancy Kerrigan and Elvis Skojko—dressed in sequined outfits—skating in a show. And, maybe, I’m remembering it incorrectly; but, somehow, men in animal costumes and 80s-era synth pop are involved. It’s undoubtedly, that Weiss, seeing something like I see, saw his future and didn’t like it. “It’s good money, but I just wanted something other than being Mickey Mouse in a fucking ice show.”

Ice skating had been like an old shoe for him—comfortable, familiar, unconscious. He was four when he first stepped onto an ice rink; and, skating, during his youth and into his twenties, was his life, his “job” as he had said. One doesn’t get rid of an old pair of shoes (or pair of skates, as it were) without getting a new pair. Walking around in socks isn’t an option. About ending his ice skating career, I have a suspicion about something; so, I ask, “Was Spain floating around in your head?” Weiss doesn’t answer immediately. It’s one of the few times he needs to explore his answer at all. He admits that, in between skating partners, he had gone to Spain to visit his sister. “It could have been,” he says. “I think so.”

——————————————————————————————————————————

——————————————————————————————————————————

Spain was on his mind—deeply on his mind, as a panoramic backdrop—seven years later, when he was writing his cookbook and trying to get signed by an agent. It can be a hard process, particularly now, with celebrity chefs and food trends having saturated the presses with a glut of cookbooks. It can be hard—but, not universally so. The difficulty is supposed to be reserved for those hawking potential titles like “My Grandmother’s 101 Italian Recipes” or “The Gluten Free Cupcakes of Brooklyn” or for whatever topic that’s really been beaten to death. Finding an agent and a publisher to sign off on a cookbook about something different, about subject matter that’s never been touched, like Spanish charcuterie, is not supposed to be much of a struggle. At least, that’s the conventional wisdom.

Spain was on his mind—deeply on his mind, as a panoramic backdrop—seven years later, when he was writing his cookbook and trying to get signed by an agent. It can be a hard process, particularly now, with celebrity chefs and food trends having saturated the presses with a glut of cookbooks. It can be hard—but, not universally so. The difficulty is supposed to be reserved for those hawking potential titles like “My Grandmother’s 101 Italian Recipes” or “The Gluten Free Cupcakes of Brooklyn” or for whatever topic that’s really been beaten to death. Finding an agent and a publisher to sign off on a cookbook about something different, about subject matter that’s never been touched, like Spanish charcuterie, is not supposed to be much of a struggle. At least, that’s the conventional wisdom.

“I got rejections left and right. I mean, “Who the hell was I?” Weiss humbly explains to me. “I was just some cook, some kid who went to Cornell.” Of course, Weiss had lived and cooked in Spain to fulfill his ICEX scholarship by that time. He had all of what that meant. But, it didn’t matter. “What was my platform? I was just a kid who went to Cornell. I didn’t have a blog.”

And, then, with my food writer’s instincts kicking in, I understand that, maybe, that was it. Weiss wasn’t a chef—yet. He hadn’t moved to Pacific Grove to helm his own kitchen. There was no Jeninni Kitchen and Wine Bar. He didn’t have the usual pedigree of being a chef and owner of a restaurant—a famous one, at that, with name recognition or like bloggers turned cookbook authors, nowadays, with thousands of followers online who can guarantee an audience.

And, then, with my food writer’s instincts kicking in, I understand that, maybe, that was it. Weiss wasn’t a chef—yet. He hadn’t moved to Pacific Grove to helm his own kitchen. There was no Jeninni Kitchen and Wine Bar. He didn’t have the usual pedigree of being a chef and owner of a restaurant—a famous one, at that, with name recognition or like bloggers turned cookbook authors, nowadays, with thousands of followers online who can guarantee an audience.

Weiss, although lacking in gestures when speaking, lifts his one hand—slightly, bolstering an already naturally persuasive voice. “In the end, it’s not just a charcuterie book. I never just wanted to write a book about how to make sausage. It’s a book about the history of this stuff. Because I’m an American writing about it, it felt incumbent upon me to tell a larger story so that it’s more than just a book about sausage. It’s a book about history, where the stuff comes from, why it’s important, and how it informs what is done today.” That’s why—aside from the obvious choice of “Charcutería” for the book’s title, he subtitled it “The Soul of Spain.”

Then, he mentions Sally Ekus, the noted cookbook agent, who eventually signed Weiss and sold his book to Agate Publishing of Chicago. “I had a 95 page proposal and footnoted the whole thing. We met at Grand Central Station for what turned out to be an hour and a half meeting; and, she signed me. She believed in me. From the proposal to when the book was released, in March 2014, it was two years.” Weiss says this with a faint sense of relief. It’s as if she had rescued the book from oblivion. Maybe, I’m injecting too much drama into it; but, in fact, in some tangible way, she had. Somebody had to believe in him.

Before Sally Ekus, Steve Chan had, of course. Weiss had consulted Chan during the proposal period. Chan remembers it well. “When he was doing the manuscript, he would email me to ask me for advice and for my opinion. I read chapter one. I said, ‘This is great.’” Chan has great admiration for the book and for what it turned out to be. “It’s a textbook on Spanish charcuterie,” he asserts. “And, I love Jeffrey’s writing style.” I love it too—how Weiss mixes crisp, academic prose, narrative passages, with bawdy interludes and makes all of that work. There’s a ballsy edge to it.

Chan thinks so too but in a slightly different way. “You know, he was very courageous,” Chan says of Weiss. “The topic of charcuterie, it isn’t glamorous. He didn’t pick a topic that was glamorous. It took a lot of balls, I think, to go in that direction. He could have done something really glitzy, you know, rather than sausage making.”

Chan thinks so too but in a slightly different way. “You know, he was very courageous,” Chan says of Weiss. “The topic of charcuterie, it isn’t glamorous. He didn’t pick a topic that was glamorous. It took a lot of balls, I think, to go in that direction. He could have done something really glitzy, you know, rather than sausage making.”

I hadn’t thought of that, but I see that Chan is right. Weiss devoted himself to his subject matter—Spanish charcuterie—and never wavered, “glitzy” or not, from presenting it to his audience, to his potential readers. It’s like the old adage states, “Sausage making isn’t pretty.” But, as a man driven by a passion, however, I don’t think Weiss really cares—not in the least.

Chan and I talk about Weiss’s book for a bit longer—long enough for us to touch upon the Gourmand World Cookbook Award, which Weiss won in the category of Foreign-International Cuisine and which had just been announced during the first week in February. Chan, who can barely muster the right words, is so outwardly proud of his protégé. “Wow, I mean, it’s crazy. I’m really happy for him.”

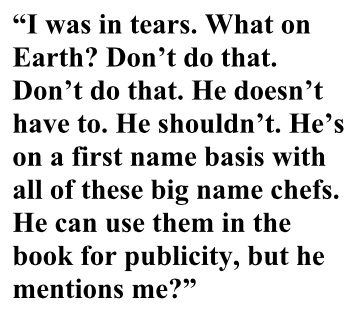

Our conversation, then—taking a different turn, with Chan still talking residually about Weiss’s recognition—segues into my recollection of Chan having been mentioned in the book. Having re-read some of the chapters just prior to meeting Weiss for our interview—in between facts about the Visigoths and Moors, admiring photographer, Nathan Rawlinson’s vivid photos, and flipping through an assortment of recipes—I saw a reference to “my mentor, Chef Steve Chan.” Weiss is making a point about Chan judging cooks by their ability to make eggs properly. Apparently, it’s a protocol that Spanish chefs use as well. I ask Chan about Weiss’s referencing him in the text.

Chan doesn’t pause. The answer is right there. “I was in tears. What on Earth? Don’t do that. Don’t do that. He doesn’t have to. He shouldn’t. He’s on a first name basis with all of these big name chefs. He can use them in the book in terms of publicity, but he mentions me?” Although I’m on the phone and can’t see his expression, I can tell that Chan’s in utter disbelief, shaking his head.

I don’t shake my head; but, what I find remarkable and commendable, given how commonplace it is in cookbook publishing today to have cookbooks ghostwritten or, at least, co-authored by a professional writer and collaborator, is the fact that Weiss wrote the whole book, nearly 500 pages, by himself.

But, knowing Weiss—who’s incisive with language and articulate—it isn’t, ultimately, surprising. He strikes me as a man who’s comfortable with a writing assignment. “I did the whole thing,” he says when I bring up the matter. “I don’t know. Maybe, it shows where I talk about comparing the ass of an Ibérico pig to the ass of Kim Kardashian or comparing my first experience with good ham to that of a good blowjob. It’s in there.” Clearly, Weiss amuses himself as he offers this and punctuates his descriptions by saying, “I wanted to write it as a cook would.”

——————————————————————————————————————————

There’s a respite in our conversation as Weiss and I dig further into the ham board that we’ve ordered at The Partisan—called, “Eternal Hamnation.” It inconsists of Italian-inspired charcuterie—Chef Nathan Anda’s house-cured prosciutto, lardo, speck, porchetta, and country ham which, in turn, we try one by one. Across from me, I can see Weiss react to a thin slice of prosciutto; his face sends out notes of approval. There’s nodding and a smile of satisfaction. There’s just enough there to make me think, “Yes, ah-ha. I understand, now, where his blowjob comment came from.”

There’s a respite in our conversation as Weiss and I dig further into the ham board that we’ve ordered at The Partisan—called, “Eternal Hamnation.” It inconsists of Italian-inspired charcuterie—Chef Nathan Anda’s house-cured prosciutto, lardo, speck, porchetta, and country ham which, in turn, we try one by one. Across from me, I can see Weiss react to a thin slice of prosciutto; his face sends out notes of approval. There’s nodding and a smile of satisfaction. There’s just enough there to make me think, “Yes, ah-ha. I understand, now, where his blowjob comment came from.”

The lardo, which is noteworthy as well, is wrapped around a tiny breadstick; and, when I bite into it, it’s salty, fatty, and crusty. It takes a few seconds to process the flavors—during which, I let out a sigh of my own and reach for more. About three feet away to my right, two women at the table next to us are intermittently glancing over at me, mumbling something indecipherable, and gawking at our food.

One of them, then, leans over and asks, “What are you having there?” She hadn’t issued the famous line, “I’ll have what she’s having,” from When Harry Met Sally. Neither Weiss nor I had succumbed to gesticulation and ecstatic expressions; there wasn’t a server around to field an immediate request. But, I feel, strangely, like Meg Ryan anyway.

“Ah,” I say. “Yes, this is the ham board.” There’s a bit of being caught off guard in my answer. It’s barely above the din in the room. “This,” I say to her. “This is the lardo and the speck…” Then, I take a bite of the speck as if she needs me to demonstrate how to eat it.

As I chew, I think back to Weiss’s book, refocus, and hear nothing but my own thoughts. “What kind of book could I write,” I ponder. Like everyone, I’m supposed to have, at least, one good book in me. And, that book, rather than being something discrete, is, supposedly, more like a garden—whose constituent ideas and inspirations are planted in bursts and spells over time: years, decades.

As I chew, I think back to Weiss’s book, refocus, and hear nothing but my own thoughts. “What kind of book could I write,” I ponder. Like everyone, I’m supposed to have, at least, one good book in me. And, that book, rather than being something discrete, is, supposedly, more like a garden—whose constituent ideas and inspirations are planted in bursts and spells over time: years, decades.

In Weiss’s case, the planting season had stretched back to those months following his retirement from skating when, with newfound purpose, he enrolled in the hospitality program at Mission College, a community college in Santa Clara, near San Jose where he had been living while skating. It was 2005. “I started at Mission College. It was a new life. I knew it was my last chance to get anywhere,” Weiss tells me as he puts down his fork. “I was so excited. I remember walking up; people were cooking. And, I said, “Yep, let’s go.”

His fascination with Spain, which had been more fuzzy than not—and without tangible manifestation—began to take shape even before entering Mission College. Weiss can’t pinpoint precisely when it happened; but, food, the notion of owning a restaurant, and being a chef had all started moving into the foreground; and, with that, the Spanish influences began to fill in as well. “I don’t think I even knew what Michael Ruhlman’s book was, but I thought about charcuterie…one of the first times that I did.” Weiss stops to reflect. “I remember,” Weiss says clearly. “I started looking things up that I liked to cook, things I liked about Spain, and chorizo kept coming up.”

Chorizo, Spain’s iconic sausage, had planted itself in his head like a viral song. It was like Beyoncé’s latest in the soft potting soil of a devoted fan’s brain. “I remember looking it up and googling, ‘What is chorizo?’ And, I realized that a lot of recipes call for this thing called chorizo. It was everywhere I looked. But, it’s really expensive because, at the time, there were no artisan butchers. Chorizo wasn’t a big thing. There was nothing. I realized if I was going to have a restaurant and have a lot of that, I should try to make it. So, back then, it was already fermenting in my head.”

——————————————————————————————————————————

The “it” could have been chorizo, specifically, or charcuterie in general—or, maybe, in the larger sense, Spanish food. That Weiss chose “fermenting” to describe what was happening isn’t lost on me. It may have been quite deliberate or just a casual choice—not unlike opening up a cabinet drawer and taking the first plate that’s stacked on top. But, in that moment, I consider the word’s literal meaning. I think of that long process of transformation when something raw slowly becomes new in a more vibrant, piquant, and complex way. Then, I notice Weiss is in mid-sentence, inexplicably—as if reading my mind—picking up on the theme of fermentation. “Wine,” I hear him say.

The “it” could have been chorizo, specifically, or charcuterie in general—or, maybe, in the larger sense, Spanish food. That Weiss chose “fermenting” to describe what was happening isn’t lost on me. It may have been quite deliberate or just a casual choice—not unlike opening up a cabinet drawer and taking the first plate that’s stacked on top. But, in that moment, I consider the word’s literal meaning. I think of that long process of transformation when something raw slowly becomes new in a more vibrant, piquant, and complex way. Then, I notice Weiss is in mid-sentence, inexplicably—as if reading my mind—picking up on the theme of fermentation. “Wine,” I hear him say.

During Weiss’s scholarship year in Spain, before immersing himself in the kitchens of Adolfo Muñoz and Dani García, there were the preceding months—a period of constant eating and imbibing. “I drank a lot of cava,” he blurts out—cava, sparkling Spanish wine. Apparently, Weiss and the others, as part of their scholarship program, had spent a month touring Spain, eating, and visiting vineyards where the wine flowed quite readily. They had their fill of it.

But, before that, there had been a month of language training first—a rather perfunctory step—at least, for Weiss since his command of Spanish was already so good. Afterwards, there was that aforementioned month of travel around Spain where Weiss and his cohorts stayed at the best hotels and dined like royalty. “We ate at all of the major restaurants,” Weiss says. He makes sure to preface his remaining remarks. “But, it wasn’t all fun and games. It was work.”

But, before that, there had been a month of language training first—a rather perfunctory step—at least, for Weiss since his command of Spanish was already so good. Afterwards, there was that aforementioned month of travel around Spain where Weiss and his cohorts stayed at the best hotels and dined like royalty. “We ate at all of the major restaurants,” Weiss says. He makes sure to preface his remaining remarks. “But, it wasn’t all fun and games. It was work.”

Most casual observers, needing that disclaimer, might not have immediately recognized it as such. The scholarship awardees got up every morning and ate breakfast and, then, they would visit a vineyard somewhere where the alcohol invariably awaited them. “Some guy would always hand us some cava right as we got off the bus. We’d walk around the vineyard and go on a vertical tasting of his cava and the wines and whatever. It’s not even 10 o’clock yet. And, then, we’d have something to eat, which would be salty. So, we’re getting more hung over.”

Lunch would follow—twelve courses at a 3 Michelin-starred restaurant where they’d eat everything only to lapse into a sluggish food coma while back on the bus and awaken from their siesta to find themselves at yet another vineyard to repeat the same litany of tastings all over again. This would be followed by dinner at a 2 or 3 Michelin-starred restaurant, of the same stellar reputation as their lunch venue, where they’d indulge in a 3 course dinner before jumping back on the bus to head to their hotel and, then—remarkably—go out for drinks afterwards as night fell. “That for a month is work,” insists Weiss. “We’re hurting. We ate so much. But, it’s important to see that. It’s an education. We needed to understand what all of that was.”

——————————————————————————————————————————

Because Weiss had endeavored to understand Spanish cuisine, deciding to work for a French-trained Chinese chef when he did—as he enrolled at Mission College and embarked on his formal culinary education—was a bit of a head scratcher. There, admittedly, is some surprise and disbelief on my part—something like, “What? A Chinese dude?”

The lessons and riches of that scholarship year in 2009 and 2010 and how that affected him were still years away and had not come to pass; but, Weiss had already visited Spain and had admitted to having Spain floating around in his head even in the waning days of his skating career. But, beginning a new chapter, that odd move to work for Steve Chan was exactly and improbably what happened.

Weiss had a good friend, Ryan Pang, who was in the know about chefs and restaurants locally; and, one day, he dropped the name, “Steve Chan.” Chan was Pang’s mentor; and, as Chan was hiring, Pang insisted that Weiss go work for him. But, then, Weiss felt the obvious incongruity of it. “I’m not going to go work for some Chinese guy,” Weiss had thought immediately. “I don’t want to cook Chinese food.” However, Pang wouldn’t give up. And, Weiss relented. The fact that Chan’s restaurant, Lion & Compass, was about 15 minutes away from the college and that Weiss needed a job made seeking out and possibly working for Chan palatable. At least, it would be convenient.

Weiss had a good friend, Ryan Pang, who was in the know about chefs and restaurants locally; and, one day, he dropped the name, “Steve Chan.” Chan was Pang’s mentor; and, as Chan was hiring, Pang insisted that Weiss go work for him. But, then, Weiss felt the obvious incongruity of it. “I’m not going to go work for some Chinese guy,” Weiss had thought immediately. “I don’t want to cook Chinese food.” However, Pang wouldn’t give up. And, Weiss relented. The fact that Chan’s restaurant, Lion & Compass, was about 15 minutes away from the college and that Weiss needed a job made seeking out and possibly working for Chan palatable. At least, it would be convenient.

Weiss tells me about the first day when he met Chan. “So, Ryan set up an appointment for me. I show up at the back door with this asshole sweater, and he was, like, ‘who is this kid?’ Then, Steve says to me, ‘No suit, huh?’ I’ll never forget it.” It doesn’t sound like the most auspicious beginning to me; and, not unexpectedly, Weiss continues his account by suggesting how Chan wasn’t impressed—how Chan’s old school, Jacques Pépin sensibilities would have wanted a complete novice, one who was looking for a job, to wear a suit and look presentable.

And, I can picture Chan’s instincts firing off warning signals—some variation of “Oh, my God! This kid’s got no kitchen training whatsoever.” If Weiss had continued with how Chan had told him to beat it and come back in three months time after he had, at least, gotten deeper into his culinary program or to just beat it entirely, I probably wouldn’t have thought twice about it. But, that’s not what happened.

After Weiss introduced himself, he and Chan talked; and, Chan realized who he was. “I remember. That name rang a bell,” Chan recalls. “I said to him, ‘You look familiar.’ Then, moments later, when I learned that he was a skater, I said, ‘Oh, yes…Jeff Weiss.’ I had heard of him. I knew of him.” I ask Chan if he had been a skating fan and had followed Weiss’s career. “No, not like that. He wasn’t a household name or anything. But, I respected the fact that he was a world-class athlete. Then, he humbled himself and came to the backdoor. He told me, ‘I want to be a chef. I want to open a restaurant.’ I said, ‘Oh, okay.’ Then, we sat down and had a chat. And, he told me about his plans.”

After Weiss introduced himself, he and Chan talked; and, Chan realized who he was. “I remember. That name rang a bell,” Chan recalls. “I said to him, ‘You look familiar.’ Then, moments later, when I learned that he was a skater, I said, ‘Oh, yes…Jeff Weiss.’ I had heard of him. I knew of him.” I ask Chan if he had been a skating fan and had followed Weiss’s career. “No, not like that. He wasn’t a household name or anything. But, I respected the fact that he was a world-class athlete. Then, he humbled himself and came to the backdoor. He told me, ‘I want to be a chef. I want to open a restaurant.’ I said, ‘Oh, okay.’ Then, we sat down and had a chat. And, he told me about his plans.”

I realize now—in speaking with Steve Chan on the phone—that in coming to Chan, Weiss had found the perfect landing spot. Chan, besides being every bit a general leading his troops, is, at his core, a teacher. It takes only a minute of talking to him to figure that out. “I think that’s why Ryan brought Jeffrey to me. I have a passion for teaching. People tried to push me to be a celebrity chef, and I flirted with it. I was a columnist for the San Jose Mercury News for a time. But, to be a famous chef, you have to leave the kitchen. And, I wanted to be in the kitchen. I love to teach. I love it. Over the years, I’ve influenced so many chefs. Who would trade fame for that?”

Taking Pang’s advice, Weiss had stashed his set of knives—meticulously sharpened ones—in the trunk of his car. It may have been Weiss rushing out to his car to retrieve them that had impressed Chan; or, it may have been Chan’s own desire to take on the challenge of making something out of Weiss—this skater turned culinary aspirant—that intrigued him. It was very likely that something in his heart, something connected to his love for shaping students into chefs, had been piqued. In any case, Weiss was hired and started that day.

“Most kids start when they’re 18. He was 28 or something,” Chan says to me in explaining what his initial thoughts were when he took Weiss on board. “We had to play catch-up essentially. I needed to accelerate his learning curve. He needed to cram in a lot of learning in a short period of time.”

The first order of business, in that regard, was learning knife skills. “I’m from the old school. Without knife skills, you can’t cook. Knife skills are everything.” Chan tells me that when he was an apprentice, all he did his first year was learn how to cut. He prepped everything for everyone in the kitchen. He’d cut and learned how to manipulate a knife until he became an expert. “I could carve roses with a paring knife before I knew how to cook.”

The first order of business, in that regard, was learning knife skills. “I’m from the old school. Without knife skills, you can’t cook. Knife skills are everything.” Chan tells me that when he was an apprentice, all he did his first year was learn how to cut. He prepped everything for everyone in the kitchen. He’d cut and learned how to manipulate a knife until he became an expert. “I could carve roses with a paring knife before I knew how to cook.”

Once Weiss put on his apron, the schooling began. Weiss’s first task, not surprisingly, was to cut onions. But, Weiss had barely begun before Chan interrupted to say, “Stop. You have to start over. You’re hurting my ears.” Weiss shows me what he was doing—using what he describes as a “guillotine motion,” a rigid stroke where the blade is perpendicular to the cutting board. Chan, then, showed him how to cut the onions properly. Weiss, similarly, demonstrates—this time, with a graceful, slightly angled motion that I can tell would have made short and efficient work of those onions.

Apparently, there were a lot of onions. “That first night, I was cutting fucking onions for eight hours or whatever it was. I cut nothing but fucking onions over and over. I had to peel them, julienne them over and over again. That repetition wasn’t by accident. It wasn’t due to the fact that Chan happened to be in possession of a lot of onions that needed cutting. Rather, forcing Weiss to engage in repetitive knife work was part of Chan’s teaching style.

It was central to how he trained his cooks. If teaching was one indelible part of his being a chef; then, engaging in hard work was the other—but, not “hard work” in that trite, every day sense. He means it in the Chinese sense—“kung fu” (which, Chan, deliberately pronounces in its proper Cantonese as “goewng foo”).

“Kung fu,” philosophically, has within it arduous practice and devotion—all of which are needed to achieve proficient skill. One’s “kung fu,” as it were, could be applied to calligraphy, pottery, welding, or, yes, very commonly, cooking—and, by extension: knife skills. Although pop culture would have us believe otherwise, “kung fu” is not an exclusively martial arts concept. Chan is a quintessential “kung fu” practitioner if the concept is taken as intended. And, by his words, it’s abundantly clear that he is.

“Kung fu,” philosophically, has within it arduous practice and devotion—all of which are needed to achieve proficient skill. One’s “kung fu,” as it were, could be applied to calligraphy, pottery, welding, or, yes, very commonly, cooking—and, by extension: knife skills. Although pop culture would have us believe otherwise, “kung fu” is not an exclusively martial arts concept. Chan is a quintessential “kung fu” practitioner if the concept is taken as intended. And, by his words, it’s abundantly clear that he is.

“I run my kitchen under the French brigade system but with Chinese principles. “I don’t teach you HOW to cook. I teach you how to BE a cook. That’s how I trained Jeffrey. You have to work. You have to train. Repetition breeds perfection. Repetition. Repetition. Right? That’s kung fu. Everyone has work to do, something to perfect.”

Chan, of course, had his own “kung fu” to worry about as well—like running a restaurant and working the line and “leading his troops.” And, as Weiss’s first day led into that night’s dinner service, that’s exactly what Chan did. However, the kitchen at Lion & Compass was laid out as such that there was an L-shaped section where Chan had his back to Weiss and was around the corner. That was where Chan stood. Weiss uses his hands—gesturing, pointing, drawing lines in the air—to show me the physical layout and to set up the punch line. “Steve would yell around the corner to me, ‘I can hear you doing it wrong.’”

There’s a distinctive sound to cutting onions. And, apparently, Weiss wasn’t close. Chan tells me there’s a “certain kind of swish” when someone’s really efficient. “Swish?” I ask, thinking that I had heard him wrong. “Yes, swish,” Chan repeats to me. All I can conjure up at that point is the sight of Michael Jordan fading back and hitting a buzzer beating jump shot. The ball goes through the hoop—slicing through the net, cutting it into thin julienned strips.

“Well,” Chan, then, adds—interrupting my mental image just as I see fans storm the court. “There’s the staccato, the rhythm too. When someone’s efficient and applying his edge properly, it’s clean. There’s a staccato. You can hear it.”

Weiss, of course, isn’t privy to Chan’s comments; and, neither am I. My conversation with Chan hadn’t taken place yet. So, we linger on these words: “He can hear me doing it wrong?” I can’t believe it either. Weiss says it, seemingly, without losing any of his original dismay. It’s as if he’s back in Chan’s kitchen. “He can hear me doing it wrong? What the fuck? Who the hell is this guy?”

Weiss, of course, isn’t privy to Chan’s comments; and, neither am I. My conversation with Chan hadn’t taken place yet. So, we linger on these words: “He can hear me doing it wrong?” I can’t believe it either. Weiss says it, seemingly, without losing any of his original dismay. It’s as if he’s back in Chan’s kitchen. “He can hear me doing it wrong? What the fuck? Who the hell is this guy?”

That last question is rhetorical, but Weiss answers it indirectly anyway. “I mean, the whole thing was very Mr. Miyagi-esque.” Weiss and I both laugh. Apparently, as time passed and he and Chan settled into their respective roles—as “master” and “apprentice” and, at that, shrouded in the kung fu philosophy that Chan undoubtedly made manifest on a regular basis—Weiss frequently and affectionately called Chan “Mr. Miyagi,” the character that Pat Morita made famous in the Karate Kid movies.

On the phone, I ask Chan about being called, “Mr. Miyagi.” “Yeah, he calls me that all the time—that and “Sifu” (Cantonese for “master’). But, ‘Mr. Miyagi,’ I don’t mind it. I know he’s just kidding, but I want him to address me as a friend, you know, and not a teacher. That’s all. But, I’m tickled by it. I’m just thankful for him even to think that of me.” Chan stops himself. For a second, I wonder if the phone line is dead. Then, I hear his voice come back—this time with a snicker. “But, the truth is, my teaching method is kind of like that.”

To me, the moniker, “Mr. Miyagi” seems to be a perfect characterization of the man because I can imagine Chan—having asked Weiss to clean a stainless steel table with two sponges. And, Weiss, begrudgingly or not, would, no doubt, have cleaned it as told by employing that classic wax-on/wax-off circular motion until his arms ached—all the while wondering, “Why the fuck am I doing this?”

Years later in his own restaurant, without Chan there and humbly volunteering, and as Weiss is scrubbing his own paella pan—it would have been a great moment to recall, relive, and understand.

——————————————————————————————————————————

The Partisan isn’t one of those restaurants where it’s so dark that it resembles a movie theater. It has large windows at the front of the restaurant that allow the glow from the streetlights to seep inside, to tease the dining room out of the night. The blonde, wooden table tops are clean, pristine and collaborate with that lighting. They provide a pleasing contrast to all of the reddish, brownish earthy food. Looking up, the walls, interchangeably of wood paneling and exposed brick, don’t turn into black holes and fade into inaccessible shadows.

As I lean into the banquette behind me, take another sip of water, and look beyond our table, there’s more than enough light to catch a glimpse of the open kitchen, which is at an angle to me. Line cooks, runners, and servers move in a busy cacophony—crisscrossing, moving out of each other’s way. It’s the height of dinner service. A plate of bone marrow, some pasta that I’m guessing is bucatini, and what appears to be lamb ribs pass in front of me. That flash of selections is a brief feast for my eyes.

Then, from my left, a man emerges from about 10 feet away and obscures the onslaught of food. He walks toward Weiss and, after a few steps, greets him. He’s a big man with a round face and a disarming presence about him. Weiss and the man talk. It’s friendly but not demonstratively so. I assume he’s a server. “Are we ordering more?”

Then, from my left, a man emerges from about 10 feet away and obscures the onslaught of food. He walks toward Weiss and, after a few steps, greets him. He’s a big man with a round face and a disarming presence about him. Weiss and the man talk. It’s friendly but not demonstratively so. I assume he’s a server. “Are we ordering more?”