(by Corbo Eng)

It’s September; and, on this day, the contractors at Thip Khao, Seng Luangrath’s new restaurant, are noisily hammering away at something in the vicinity of the restrooms. One of them purposefully schleps out of the front door with a roll of carpeting or a large floor mat on his shoulder like a butcher might carry a pig’s carcass. Luangrath, who is preoccupied with the dining room furniture and contemplating how best to execute the restaurant’s décor, barely notices the contractor walk by her. “When we finally open, I don’t want people coming in and just seeing Thaitanic II in their minds,” she says. “It has to be different and fresh.”

It’s September; and, on this day, the contractors at Thip Khao, Seng Luangrath’s new restaurant, are noisily hammering away at something in the vicinity of the restrooms. One of them purposefully schleps out of the front door with a roll of carpeting or a large floor mat on his shoulder like a butcher might carry a pig’s carcass. Luangrath, who is preoccupied with the dining room furniture and contemplating how best to execute the restaurant’s décor, barely notices the contractor walk by her. “When we finally open, I don’t want people coming in and just seeing Thaitanic II in their minds,” she says. “It has to be different and fresh.”

What’s gnawing at her the most aren’t the brash orange chairs that once graced Thaitanic II, a Thai restaurant whose space she has inherited, but the tables. She doesn’t like them—their glossy, lacquered finish that seem out-of-place with what Luangrath probably envisions as a more restrained interior without any garish overtones. “Do you know where I can get wooden tabletops?” she asks me. Not having purchased restaurant furniture before or thought about tabletops, for that matter, it’s not a question I can quickly answer. I literally scratch my head. But, it doesn’t matter.

By the time, Thip Khao opens its doors with buzz and fanfare—two months later—it will, indeed, boast some fine wooden tabletops, the kind that are handsome and solid and that one wouldn’t hesitate to knock on for good luck. However, it isn’t luck that’s gotten Luangrath to this point, nearly five years into her tenure as a chef and restaurateur, during, which time she, branding herself as “Chef Seng,” has become one of the foremost immigrant chefs in the DC area. Really, what has ensured Luangrath’s success is a lot of perseverance—the kind that luck, anthropomorphized into a living being, would envy as a stronger version of itself. But, Luangrath, shaking her head, can’t believe how far she’s traveled and how, incredibly, she’s the one who will finally open DC’s first Lao restaurant.

Thip Khao, in many ways, is the culmination of a vision, a personal vision to bring the food of her homeland from out of the culinary shadows. And, no amount of dumb luck would have made that happen. In fact, it didn’t take long for Luangrath, when I chatted with her back in August, to reveal that what’s really at play is a sense of purpose—and a deep desire to realize it. Her voice, so resolute at the time, gave it away. “So many people I talk to don’t even know where Laos is or its history and foodways,” she said. “Many are familiar with Thai food, of course; but, they don’t realize that a lot of what they know as Thai food really has its origins in Laos. I try to explain this, to educate people about Lao food.”

Thip Khao, in many ways, is the culmination of a vision, a personal vision to bring the food of her homeland from out of the culinary shadows. And, no amount of dumb luck would have made that happen. In fact, it didn’t take long for Luangrath, when I chatted with her back in August, to reveal that what’s really at play is a sense of purpose—and a deep desire to realize it. Her voice, so resolute at the time, gave it away. “So many people I talk to don’t even know where Laos is or its history and foodways,” she said. “Many are familiar with Thai food, of course; but, they don’t realize that a lot of what they know as Thai food really has its origins in Laos. I try to explain this, to educate people about Lao food.”

Having exhausted the topic of tabletops—at least for now—Luangrath’s attention has turned to the fresh coat of paint on the dining room walls: an ochre that leans slightly more toward the yellow side and that, I reassure her, is a fine choice. Then, pointing to the far wall where there are several recessed nooks, one that displays a pot left over from Thaitanic II and where there’s a conspicuous empty space that’s calling out for something to cover it, Luangrath doesn’t expectedly educate me on Lao food but on its culture. “Over there, I’m going to have an artist paint a big picture of a naga. It’s a snake-like serpent from Buddhist tradition that’s a really important part of Laos,” she explains. “It’s a symbol of the country, really.”

Wordlessly at attention, she stands still. Looking straight ahead, I can see that she’s imagining the naga there on the wall in its finished state. Not having a point of reference, I can’t see it; I can’t feel its import—not until the artwork is finished months later and the multi-headed serpent, with each of its mouths wide open, teeth bared, tongues extended, is at attention. Then, I understand. Now, standing beside Luangrath, the silence catches me suddenly. It’s an ellipsis in a long poem; and, all I can sense is how meaningful it is that her dream of opening a restaurant, devoted solely to serving Lao food, is finally coming true.

—————————————————————————————————————————-

In March of 2010, when Luangrath and her husband, Boun, bought Bangkok Golden—a solid if not unnoteworthy Thai restaurant in a nondescript strip mall in Falls Church, Virginia—becoming the focal personality on Lao food in the DC area would have been a total fantasy. She had the modest goal of simply, but finally, cooking professionally. During the preceding decade, she had languished in jobs that she didn’t like where her talents as a cook went untapped—working as a bank teller, for example, or performing managerial and administrative tasks for a carpet and flooring business where Boun worked and later his contracting company. “I was miserable,” Luangrath says thinking back on her work history. “I didn’t know anything about carpets, floors, or construction. I learned. But, it wasn’t my passion.” She had a brief stint where she catered parties for her husband’s business associates. It was during this phase that the refrain, “Why don’t you open a restaurant?” from bemused friends and family became all too familiar and frequent. She knew it was time.

Bangkok Golden had been Thai owned and served Thai food—all of the familiar curries and Chinese-inspired stir-frys that have come to characterize Thai food in the United States. “I was prepared to just cook Thai food,” Luangrath recalls. “I’d never owned a restaurant before, and I knew that the failure rate for restaurants was pretty high. I didn’t want to change too much from what the previous owner did. They served a buffet during lunch that was pretty popular—offering pad thai and such. So, I kept that. But, here and there, customers would ask me about Lao food. I introduced daily specials and talked them up to the customers. That’s how it started.” The progression, frankly, was locomotive-fast. By April—just a month into her ownership—Chef Seng began serving Lao food off-menu.

In this day and age, word can spread fast; and, that’s exactly what happened online as Yelp reviews, discussion boards, and foodie chatter began pointing to the off-menu Lao food in the unassuming strip mall Thai joint over in the Seven Corners section of Falls Church. It all came to a head in November of that year when iconoclastic Washington Post food critic, Tom Sietsema, lured in by all of the mounting fuss, wrote a solidly positive review of the restaurant—focusing not on the Thai selections but the Lao food. At one point, citing the presence of lemongrass, galangal, limes, and chilis, he struck a familiar tone; but, then, describing a tangle of incendiary flavors and extolling the “murky, volcanic” make-up of the Lao-style papaya salad with its unusual shrimp and crab pastes, Sietsema, enjoying a dining experience unique to the DC area, pointed toward something very different and gave Luangrath’s food and the food of Laos, obscure to most Post readers at that time, a nice dual shot of legitimacy.

Additionally, his two-and-a-half star (good) review was well-timed—as Luangrath was eager to finally roll out a full Lao menu of about 30 items. Once launched, the Lao menu became an immediate fixture and Bangkok Golden’s much touted calling card. The crowds came; and, nobody was more surprised than Luangrath who found herself, suddenly, at the center of so much attention. It was rewarding if not a bit puzzling all at once. “To me, this is the food I grew up eating. It’s often smelly, always spicy, and so different than what most people are used to eating. I didn’t think my customers would like Lao food.”

—————————————————————————————————————————-

Last summer, the fact that her customers liked (no, loved) her food was made very tangible and in a way that regular post-meal praise and accolades from patrons or even Tom Sietsema, spreading his approval in The Washington Post, couldn’t. Her food, having won fans and adherents with its exotic template of flavors, had proven that it could draw people comfortably in and leave an impression. But, this time, having been invited to cook at a private function, it was different.

Luangrath was standing in the kitchen of someone’s home, cooking for a special event, which had been disguised as a birthday party for a friend of a bride-to-be but that was, in fact, an engagement party that Josh, a regular customer at Bangkok Golden, had arranged as a surprise for his girlfriend. She had taught English in Isan, in Northeastern Thailand, where Lao food is ingrained into the region’s food culture. Anna, the aforementioned bride-to-be, greatly missed the spicy, palate-burning flavors that she had grown to love in between helping students conjugate irregular verbs by day and grading papers by night. Seeing the unexpected sight of Chef Seng standing there with the food that she had prepared for the occasion—food that took her back to Isan and to the many times she had visited Bangkok Golden with Josh—was emotionally just too much to bear. There was a spontaneous embrace in the kitchen; Anna cried; Luangrath too. “It was so rewarding,” Luangrath explains now. Clearly, that day resonated. The emotions are fresh. “I love it when I can make people happy. I want to share my food and have people experience it. When they like it, sometimes, I can’t believe it. Anna isn’t even Lao. That makes it so much more satisfying.”

Luangrath was standing in the kitchen of someone’s home, cooking for a special event, which had been disguised as a birthday party for a friend of a bride-to-be but that was, in fact, an engagement party that Josh, a regular customer at Bangkok Golden, had arranged as a surprise for his girlfriend. She had taught English in Isan, in Northeastern Thailand, where Lao food is ingrained into the region’s food culture. Anna, the aforementioned bride-to-be, greatly missed the spicy, palate-burning flavors that she had grown to love in between helping students conjugate irregular verbs by day and grading papers by night. Seeing the unexpected sight of Chef Seng standing there with the food that she had prepared for the occasion—food that took her back to Isan and to the many times she had visited Bangkok Golden with Josh—was emotionally just too much to bear. There was a spontaneous embrace in the kitchen; Anna cried; Luangrath too. “It was so rewarding,” Luangrath explains now. Clearly, that day resonated. The emotions are fresh. “I love it when I can make people happy. I want to share my food and have people experience it. When they like it, sometimes, I can’t believe it. Anna isn’t even Lao. That makes it so much more satisfying.”

Local chefs of note—all non-Lao themselves—as curious and enticed as any group of food enthusiasts, embraced the Lao menu as well, beginning in 2010, once the word on Bangkok Golden began to spread. Luangrath, understandably, beams with pride now when recalling those in the local fraternity of chefs who have come through Bangkok Golden’s doors. She gives me a sample of names: Eric Ziebold of CityZen, Cedric Maupillier of Mintwood Place, Haidar Karoum, chef at Proof, Estadio, and Doi Moi, Andy Bennett of Lyon Hall, and Cathal Armstrong of Eamonn’s and Restaurant Eve fame.

Exactly three years after taking over Bangkok Golden, in March 2013, as a sign that she had expanded her influence and caught the attention of gastronomes in DC, no less a local figure than Eric Bruner-Yang of the popular ramen shop, Toki Underground, arguably the city’s trendiest restaurant, had invited Luangrath to cook at Toki for one night as part of a “Taste of Laos” takeover of his restaurant. Luangrath, serving a $50 six course tasting menu of her biggest hits, brought the house down. The guests who gathered at Toki that night on H Street—many of whom would rather have stayed home to eat leftover Chinese food than cross the mentally imposing boundary of the Potomac River to dine out and make a evening of it—loved her food and the event. It was a win-win situation. Folks in the DC dining scene got a taste, both literally and figuratively, of a new cuisine—a cuisine, exotic and hip, that planted the seed for future cravings. Luangrath, so pleased by how the night had gone, met and served a new audience and was, for that moment as a professional chef, as far away from the suburban throes of Falls Church and Bangkok Golden as she had ever been.

—————————————————————————————————————————-

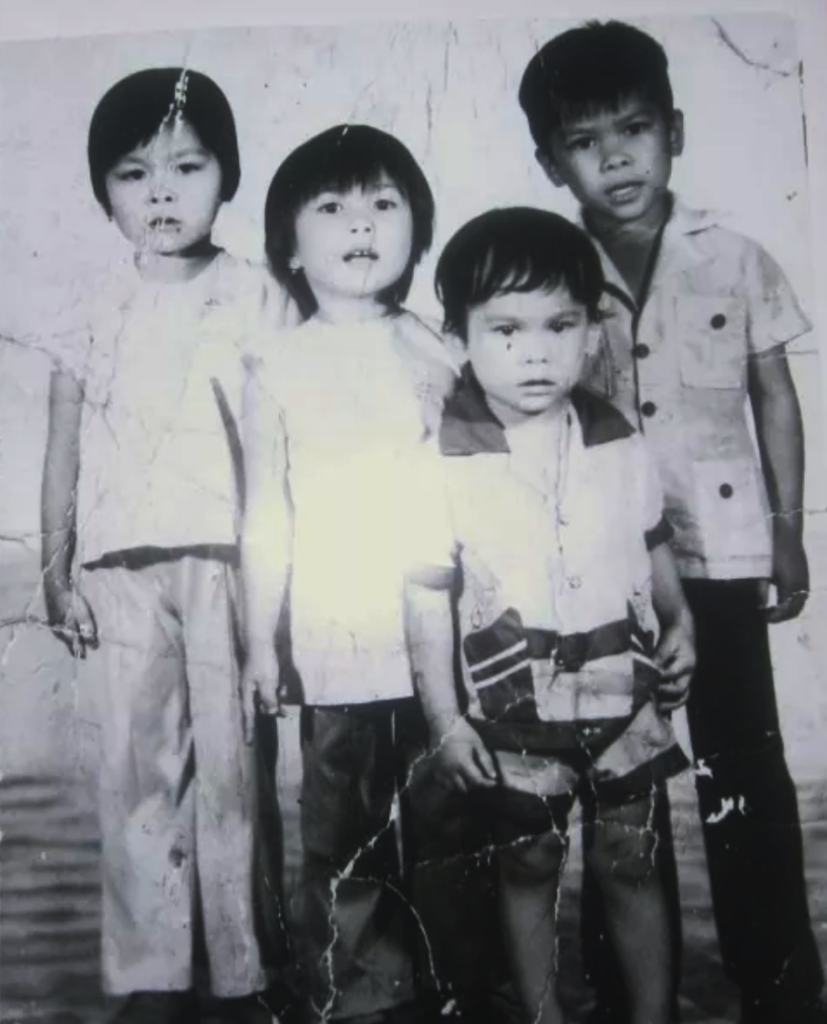

Seng Luangrath came to the United States in 1983, when she was 14, as a refugee from Laos, with her mother, her step-father, her half-sister, who had been born in the refugee camp, and her two brothers, and landed in Berkeley, California where her aunt, the family’s citizenship sponsor, resided. The family lived in a comfortable if not unspectacular apartment—cramped quarters, really, for a family of five. But, Luangrath’s parents worked two jobs and were seldom home, allowing the children free reign, until late at night. Even though one of her brothers was older, Luangrath, as the oldest girl, was charged with taking care of the home and making sure everything was in order, which meant cooking and having dinner ready once her parents returned from work. Her mother who ran a very strict, regimented household was unwavering about this duty. “My mother was very conservative,” Luangrath explains. “A girl’s place was in the home—not outside where there was certain trouble. For boys, it was different.” Consequently, Luangrath was prohibited from doing much outside the home—except go to school.

However, rather than chafe under what most would have regarded as draconian strictness, Luangrath, instead, thrived under these conditions. It was all because of her love of cooking, which she had cultivated from a very early age. “I was passionate about cooking,” she says. “I think I would have eventually gone down the road of being a chef even if my mother hadn’t required me to cook like she did. The roots of my love affair with cooking started long before we got to Berkeley. But, you could say that she shaped me to become who I am today.”

By 1986, when she was 17, Luangrath’s repertoire of dishes spanned the entire spectrum of Lao food to include the usual comfort foods and extracurricular exploits that would mark a very accomplished home cook—one who prepared meals for family and house guests, certainly, but for special occasions as well in the Lao community, such as birthdays and weddings. Luangrath did all of this happily and with joy. When her mother arranged for Luangrath to marry her now-husband, Boun, a friend of her step-father’s, in 1986 and when they finally wed in 1989 after a long engagement, Luangrath—ever in demand—actually cooked at her own wedding where she helped prepare food for some 300 invited guests. It was Luangrath’s passion for the kitchen that had so attracted Boun to her in the first place. He had never seen a young woman who was so enamored with cooking.

In 1989, she moved to the DC area—to Northern Virginia—where, instead of cooking for her parents and siblings, she now cooked for her new husband and his extended family: her brother and sister-in-law and her husband’s aunt and uncle. It was a seamless transition that was made all the more smooth by the same skills and talent for cooking that allowed Luangrath to flourish as the family cook back in Berkeley. “I was a classic housewife at that point—cooking for me and my husband’s family, for all of us who lived in the same house. But, also…every weekend, all of my husband’s other relatives in the area would come over. We would have these really big get-togethers where I’d be in charge of the food. It was the best kind of training, and it really wasn’t that hard.”

—————————————————————————————————————————-

The hardest thing, of course, had been to get to the United States in the first place. It was 1981, and Luangrath was 12 years old—living in Vientiane, the Lao capital, in a matriarchal household led by her maternal grandmother. Six years had passed since the communist takeover of the country in 1975. The ruling Pathet Lao, during this still tumultuous period were hunting down those they had labeled as traitors and collaborators. Luangrath’s father who had worked for the military and who had been loyal to the anti-communist forces, including the Americans, had been sent to a labor camp in an undisclosed location. Naturally, under such an intimidating climate where families of the hunted, certainly, weren’t immune from retribution, Luangrath and her family didn’t feel safe—even though her parents had divorced years earlier. Erring on the side of caution and urged on by her grandmother, the family (consisting of Luangrath, her mother, and her two brothers) fled the country.

The hardest thing, of course, had been to get to the United States in the first place. It was 1981, and Luangrath was 12 years old—living in Vientiane, the Lao capital, in a matriarchal household led by her maternal grandmother. Six years had passed since the communist takeover of the country in 1975. The ruling Pathet Lao, during this still tumultuous period were hunting down those they had labeled as traitors and collaborators. Luangrath’s father who had worked for the military and who had been loyal to the anti-communist forces, including the Americans, had been sent to a labor camp in an undisclosed location. Naturally, under such an intimidating climate where families of the hunted, certainly, weren’t immune from retribution, Luangrath and her family didn’t feel safe—even though her parents had divorced years earlier. Erring on the side of caution and urged on by her grandmother, the family (consisting of Luangrath, her mother, and her two brothers) fled the country.

On a dark, forboding night—one that was marked by the harrowing wee hours of the next morning—with her younger sister left behind to care for her grandmother, Luangrath made her way down to the nearby Mekong River with her family. The air was eerily still, tense, and filled with anxious humidity. Her uncle acted as their handler and guide—escorting them through miles of darkness where vague outlines were a portent of danger and sounds were unsettlingly and disproportionately magnified. Trusting him, they followed and rushed to a remote part of the riverbank, past the reach of the urban lightscape, where they hid in a makeshift hut by the water to wait for an opportune time to cross the river into Isan on the Thai side.

Luangrath, as if tapping a memory bank, remembers the scene, “It was about 4 a.m. when it appeared safe, and we ran out of the hut and got into a small boat that my uncle had arranged for our use. So, we crossed. Fortunately, in this remote part of the Mekong in the countryside, the river wasn’t too deep. There was this embankment or high ground in the middle of the river where we stopped for a moment. Then, we heard gunshots in the distance. I was so scared. The rest of the way was very marshy, and I could actually stand up with the water up to about my shoulders. So, I ran through the water the rest of the way.”

Once in Thailand, she and her family weeded through dense forests and found refuge in a villager’s house. However, by morning, the Thai authorities had found them. Eventually, they were sent to the Nong Khai refugee camp where they stayed for about three months. The rural camp was a dusty, rudimentary settlement of bamboo buildings with thatched roofs that lacked any amenities or running water. The food, very much accentuating the spartan feel of the camp, provided sustenance and nothing else. Meals consisted of boiled cabbage, rice, and on the rarest occasion, some pork.

From Nong Khai, Luangrath and her family were transferred to a permanent camp in the neighboring province of Nakhon Phanom. There, in a more sprawling space, the camp buildings were still constructed of bamboo, and the roads were still formed from packed dirt rather than paved; but, the camp’s occupants had access to running water, which alleviated some of their hardships. But, most consequentially, the food at Nakhon Phanom was just so much better. The refugees benefitted from humanitarian food donations from international organizations; but, the real blessing was the fact that they had access to local meat and produce. The camp itself was segregated off from the surrounding Thai villages by barbed wire fencing—which, through its gaps—the locals and the refugees, occupying opposite sides of the fence, were able to barter, trade, and exchange items of all kinds.

From Nong Khai, Luangrath and her family were transferred to a permanent camp in the neighboring province of Nakhon Phanom. There, in a more sprawling space, the camp buildings were still constructed of bamboo, and the roads were still formed from packed dirt rather than paved; but, the camp’s occupants had access to running water, which alleviated some of their hardships. But, most consequentially, the food at Nakhon Phanom was just so much better. The refugees benefitted from humanitarian food donations from international organizations; but, the real blessing was the fact that they had access to local meat and produce. The camp itself was segregated off from the surrounding Thai villages by barbed wire fencing—which, through its gaps—the locals and the refugees, occupying opposite sides of the fence, were able to barter, trade, and exchange items of all kinds.

“The people who came to the fence were opportunists mostly,” Luangrath points out. “They would come to the fence carrying their wares in baskets…baskets that they tied to a bamboo pole that they balanced on one shoulder. Luckily, our family had some money that had been sent to us from my aunt. We used that money to buy things like beef and small fish, which we ate fried. Most of the refugees had no money. So, there were these trades where they would give the villagers some camp-issued soap and toothpaste for herbs, vegetables, chicken, or eggs. The villagers were pretty accommodating. The best thing was being able to trade a bunch of those cabbages that we were so tired of eating for some Chinese sausage.”

Cooking was strictly an outdoor endeavor. There was a designated area that was set aside for cooking where each of the refugee families prepped their own food and, using traditional braziers, cooked it in woks or on metal grates over hot charcoal. These short, stout earthenware ovens, which might have reminded the uninitiated of planters used to grow flowers or small trees, were lined up in a row so that the women, each cooking for their own families, sat or squatted next to each other as they tended to their food—making such dishes as Lao beef stew or banana-leaf wrapped steamed fish with dill. It was the perfect set-up for anyone who wanted to see and learn. With little to do and driven by her own intense interest, Luangrath, like a hawk more than a spy, observed the women at work and took in all of the minutiae and fine details. Before long, she became the de facto cook for her family. As the dust blew in off the dirt roads and as the unrelenting afternoon heat hovered over the camp, Luangrath cut vegetables, chopped lemongrass, toasted rice powder, or pounded chilis until her hands ached from the precision that those tasks required and as the chilis, turned into something like a mace aerosol, burned her eyes. But, she never complained. She knew that she had found something like home.

—————————————————————————————————————————-

Sitting across from me at the corner table near Bangkok Golden’s front door, Luangrath has another set of reminiscences. The harrowing and harsh descriptions that fell from her lips yield to something more gentle and serene. She pauses and takes a sip of water. Her mind turns back to Vientiane. “Where I lived with my family,” Luangrath remembers. “There was a garden that I loved. We had the right weather, and we could grow so much. We used most of it.” She recalls that garden with great fondness—the idyllic setting, with the river and ponds nearby, and the ease with which she could go there and pick ingredients and herbs as if they had come directly from the heavens. She has a look of daydreams. The recall of the past becomes present; and, her thoughts intermingle. “I have a home garden now.” In fact, anyone following Chef Seng on Twitter or Instagram would know this well—what with her regularly posting and tweeting out photos of leafy greens and obscure herbs as a mother might show off pictures of her children.

In between words, Luangrath peers back toward the kitchen. Her eyes light up as she turns around. Out of the corner of my eye, I quickly glance out at the dining room, at the steam tables set up for the buffet to the right, and see that the lunch rush has rapidly wound down. It was a particularly busy afternoon; but, I know that’s not what has her attention. “I have these ginger leaves that I grew in my garden,” she suddenly explains to me gleefully and gives me an outline of their shape and form with her hands. “These leaves are great, and it’s the first time that I’ve really grown them.” Of course, I’ve never heard of such leaves and am puzzled by what they are. Luangrath yells to Bobby, her son—who’s standing in the back—to get the leaves from the kitchen.

A minute later, Bobby returns. “Look,” she says as she points to a slender leaf, robustly green, that tapers to a point at both ends. To me, it looks undistinguished and like something I might unknowingly step on in the woods—or on a traffic island in a parking lot somewhere—and, at which I wouldn’t bat an eyelash. Luangrath takes the leaf and smells it. Then, breaking off a corner, she takes a bite and offers a piece of it to me. “Hmm…it tastes just like ginger,” I say surprisingly. I should have known. The look on Luangrath’s face is one that tells me she’s devising a daily special for tomorrow’s menu in order to take advantage of her special bounty. But, then, she says, “Please, take them home.” For a second, I see myself haphazardly stir frying them—by default—but, I can’t take her up on her generous offer. Instead, as with the naga later on when I’m at Thip Khao months later, Luangrath has me engrossed in her words. Only, now, with the August backdrop beginning to fade—but, still, more timely than not—she educates me on ginger leaves.

“My mother and younger sister were not that interested in cooking,” Luangrath continues. So, growing up, my grandmother was in charge of the kitchen and cooked all of the family’s meals. But, I was always curious about what was going on in there. I was shy; and, while my siblings played outside with the neighborhood kids, I stayed in the kitchen and watched my grandmother cook.” Eventually, due to her curiosity and her persistent presence in the kitchen, Luangrath was recruited to help out. “I was genuinely fascinated by cooking and wanted to learn,” she clearly recalls. “My grandmother would prepare the stuff that we grew in the garden. Each ingredient and herb was handled differently. I focused on each one in turn as my grandmother used them for the different dishes that she would make.”

By age eight, Luangrath was tasked with making the sticky rice. It required washing and, then, soaking the raw grains of rice overnight and getting up early in the morning to cook it in a traditional bamboo steamer basket over a pot of boiling water. As the sticky rice was the staple food—and something that would be eaten throughout the day—being responsible for making it was no small matter. Such a responsibility was a source of pride, for sure—one that led to other tasks such as being assigned to shred and pound the green papaya with a mortar and pestal to make papaya salad. “It was a lot of fun,” Luangrath remarks.

Her biggest thrill, however, was making one of her favorites called, “koong ten.” “It’s an example of a ‘laap’ or Lao salad,” Luangrath explains. “All laaps have herbs like lemongrass, kaffir lime leaves, mint, and other ingredients like long beans, sometimes, chili and shallots, that make them up. There is usually a meat that is minced and mixed in with the other ingredients. The best known laaps have beef or pork in them. The meat, like the herbs, is chopped very finely and, often, served raw in the final mixture.” She pauses for a second and then offers the punchline. “Koong ten is laap like any other, but it just happens to be made with live baby shrimp. The shrimp wiggles around a lot on the plate, so the dish is known as ‘disco shrimp.’”

It’s a catchy moniker; but, making the koon ten was an adventure to be sure, which, undoubtedly, contributes to its being so keenly remembered. “It was my absolute childhood favorite,” Luangrath admits unequivocally. “I miss it so much.” On rainy days, when the rain or drizzle would hit the water and agitate it, Luangrath would head down to a pond near her house to collect the shrimp. Each was about an inch long and a quarter of an inch in width. They were grayish, almost transparent—as if they had been birthed by lightening itself.

“I had this strainer or sieve that was like a cheesecloth that I used to catch the baby shrimp. For bait, I used rice husks that I had soaked in fish sauce. The shrimp loved that stuff.” Once caught and mixed into the laap, the shrimp, still alive, of course, would twitch incessantly—showing off their “disco” moves. “Sometimes, the shrimp would jump away, but I ate the koong ten wrapped in lettuce or on betel leaves. In that case, the shrimp had a hard time escaping.” She pauses for a moment. A light bulb turns on in her head. “If I could find a supplier with this kind of shrimp, I would really think about serving koong ten regularly at Thip Khao.” She laughs as if second guessing herself. “But, I don’t know if people will like shrimp dancing around on their plate.”

—————————————————————————————————————————-

By the early weeks of November, it’s Thip Khao’s soft opening period, and Chef Seng’s Instagram and Twitter accounts are studded with photos of her inaugural dishes—Lao style deviled eggs with dried river weed, tapioca balls with peanuts, radish, and cilantro, and salmon steaks grilled and wrapped in banana leaves are some of the highlights. The only shrimp in sight aren’t of the “disco” variety but, instead, large, plump ones, cooked, of course, and that are served with chunks of mango to adorn her fried watercress salad. The invited guests each night, as they nonetheless survey the menu, are quite unaware that they could have been dining on live shrimp—however remote the possibility was.

The food that they are served, plated on rustic wooden boards and shiny white geometric plates, is a glorious representation of Lao cuisine and, without tension, balances the forces that created it—Luangrath’s need to work out the kinks in her ideas and her desire to flawlessly impress her guests. The pressure to get everything just right would be present enough with curious strangers walking in off the street; but, with familial ties, friendship, loyal patronage, and simple, unadulterated respect all exerting themselves like vectors in the dining room, the pressure is, rather, intimidating but oddly exhilarating too. It’s a special time. Luangrath—working behind the scenes each night—anxiously prepping the food, supervising her new staff, and, yes, cooking too, can peek out from the opened entrance of the kitchen or leave the kitchen altogether, at her discretion, to survey the scene.

The food that they are served, plated on rustic wooden boards and shiny white geometric plates, is a glorious representation of Lao cuisine and, without tension, balances the forces that created it—Luangrath’s need to work out the kinks in her ideas and her desire to flawlessly impress her guests. The pressure to get everything just right would be present enough with curious strangers walking in off the street; but, with familial ties, friendship, loyal patronage, and simple, unadulterated respect all exerting themselves like vectors in the dining room, the pressure is, rather, intimidating but oddly exhilarating too. It’s a special time. Luangrath—working behind the scenes each night—anxiously prepping the food, supervising her new staff, and, yes, cooking too, can peek out from the opened entrance of the kitchen or leave the kitchen altogether, at her discretion, to survey the scene.

It’s a Thursday night; and, the dining room is filled. Bandith, an amiable front-of-house staffer, greets my party and shows us to our table. He’s happy and warm and talks up the food accordingly; but, otherwise, given the festive occasion, we joke about some disparate and lighthearted matters until I order, he leaves to attend to other guests, and the evening, stepping forward, pushes back an invisible curtain to reveal a showcase of selections, each arriving in turn—an accompanying round of fresh greens and herbs with a dish of sweet/spicy dipping paste, the deviled eggs that I’ve seen several photos of the last few days, grilled pork shoulder, and smoked eggplant curry.

But, something else, however, has my attention momentarily. From where I’m sitting, I have a clear view of the bar and the shelving behind it where neat rows of bamboo baskets—the namesake “thip khaos” that are used to serve sticky rice—are displayed like museum artifacts. Cylindrical but slightly bulging in shape, these, about six inches tall, are finely woven and are lit by ambient light into wondrous vessels of beige and gold. The colors, registering in my eyes, follow me back to the thip khao on my table where, now, focusing on the food, I reach to pull out the sticky rice.

Copyright 2015 (Corbo Eng). All rights reserved.

Photos courtesy of Seng Luangrath and Gena Roma Photography